Track 1 - Tyler City: The Depot and the History

Tyler City - The Depot

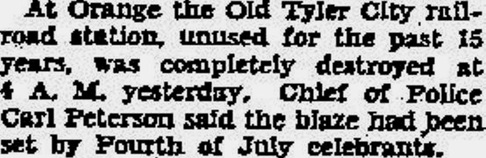

[1.00] Dateline: Orange, CT, July 5, 1936

This elusive piece of information was found in a New Haven Sunday Register article [NHSR/07/05/1936/02] in files at the Orange Historical Society. It is unclear to us whether yesterday means 4:00 a.m. in the wee hours of 7/4/1936 or on after midnight which would actually make it on 7/5/1936.

This elusive piece of information was found in a New Haven Sunday Register article [NHSR/07/05/1936/02] in files at the Orange Historical Society. It is unclear to us whether yesterday means 4:00 a.m. in the wee hours of 7/4/1936 or on after midnight which would actually make it on 7/5/1936.

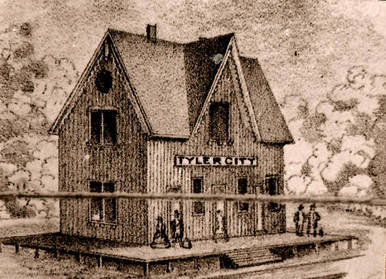

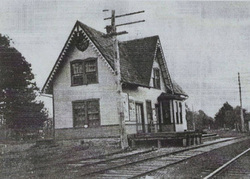

[1.0] This view of Tyler City station scan from OHS [click here] is probably the only photo in existence that shows life at the depot, if not actual people. We speculate that the date is early 1888, sometime after January 16, when the new operator, the Housatonic RR, added a 7:30am train from New Haven that would have passed Tyler City at 7:50 as shown on the 'Dutch clock.' With the other face unseen here, the 'clock' alerted engineers operating in both directions to keep their distance behind the preceding train. Also referred to as a "time case," this safety device was in use all along the the HRR by 1890 [CWN/06/25/1890/03] and seems to date back to 1874 on the NYNH&H [NHDP/07/21/1874/04]. A 13-mile NH&D running six daily trains each way did not really need this but, with the Extension added in 1888 and fifty trains a day running by 1892, it was indispensable. The clock worked simply by having day-of-the-week, train-type, and time-number cards changed by the station agent. His presence and use, possibly with family, of the living quarters upstairs is verified by the laundry hanging out of the east windows. A significant absence in this photo is the bay window where the agent would observe trains, send telegraph messages, and sell tickets. With stations at Orange, Derby Jct., and Birmingham [see Track 4A, MP 4.47, 4.67; Track 4B, 4.63] also not showing them, the early NH&D seems to have done without. The iconic Bell telephone sign at the doorway, the roof discoloration, and the bay window to come all argue for the later, ca. 1888, date and pending upgrades by the HRR.

[1.1] This picture is perhaps shortly after the June 13, 1925 discontinuance of passenger service. The bay window is in place as are the main line, passing siding, and the freight platform with track to it, but the Dutch clock is no longer seen. We assume that the NYNH&H kept it in use after 1892 when it leased the HRR and the NH&D and continued to run a dozen or more passenger trains per day each way in addition to freight movements. Those days seem to be gone in this eerily quiet scene.

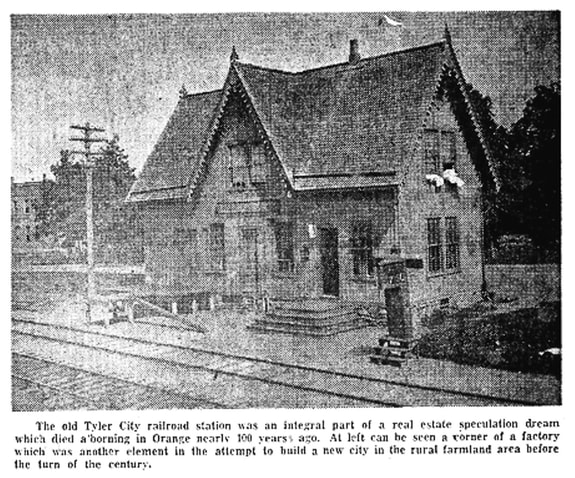

[1.2] This shot was presumably taken late in 1929 when it appeared in a Register feature article [NHER/10/27/1929/03] on Tyler City entitled "'Gateway to the West' is Ghost City Now." It says that "The depot kept up by the railroad until recently now furnishes a roost for birds." The Tyler City signboard, the platform with what may be a freight wagon in the far left, and the Bell telephone sign all give the appearance of some degree of service, as does the car parked in the lower right, but the bay window is now boarded up. Since this portion of the NH&D was not abandoned until 1938, we have to assume that the mainline is out of sight here. It is believed to have been removed in the early 1940s for the steel that was needed in the war effort.

[1.3] This shot was taken between 1930 and July 4, 1936. It appears on page 109 in the book Connecticut Railroads, which was published by the Connecticut Historical Society in 1986. The depot may be still be in use as a residence with the assorted implements seen on the ground, but with windows on the ground level boarded up as seen in the 1929 photo. The Tyler City signboard is still in place but the Bell telephone sign is gone as is the freight platform and the rails up to it. The small building, perhaps the outhouse, is seen in the lower left. The last listing for the NYNH&H station in Tyler City is in the 1931 Price & Lee Milford-Orange city directory.

Tyler City - The History: Connecticut's 1870s Railroad Boom Town

[1.4] Our website name derives from the still-quiet area in the town of Orange where Tyler City came into being in 1872. The New Haven and Derby RR had just opened on August 9, 1871 to offer better freight, passenger, and mail connections between the Elm City and the Naugatuck Valley. Hitherto, rather roundabout service was provided by the Naugatuck and the New York and New Haven RRs via Naugatuck Jct., today Devon, a circuit that was twice as long as the NH&D's ten miles. The 'Little Derby' was going to save time and lower costs and a boom town was expected to grow up by the railroad that was touted as the 'Gateway to the West,' a west both near and eventually far, to Danbury, the Hudson River, and beyond.

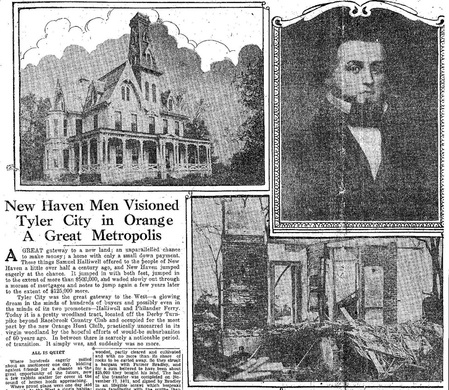

The fullest recounting of the "The Tyler City Bubble," as she calls it, is by Mary Rebecca Woodruff, a long-time resident. Her book has been digitized by the Case Memorial Library, appropriately located on Tyler City Rd., popular use of this name undoubtedly beginning in 1872.1 Additional detail comes from the 1929 Register article mentioned above, and a follow-up piece in the Evening Sentinel, as well as many other sources we have consulted to put together an all-time, definitive history.2 As much as the talk has gained favor about the bubble that burst and Tyler City's seeming lack of importance, we have found events of significance that may put it on the map as it has never been before. More will be found at Track 2, MP 2.2.4 and Track 4A, MP 4.41-4.43.

The fullest recounting of the "The Tyler City Bubble," as she calls it, is by Mary Rebecca Woodruff, a long-time resident. Her book has been digitized by the Case Memorial Library, appropriately located on Tyler City Rd., popular use of this name undoubtedly beginning in 1872.1 Additional detail comes from the 1929 Register article mentioned above, and a follow-up piece in the Evening Sentinel, as well as many other sources we have consulted to put together an all-time, definitive history.2 As much as the talk has gained favor about the bubble that burst and Tyler City's seeming lack of importance, we have found events of significance that may put it on the map as it has never been before. More will be found at Track 2, MP 2.2.4 and Track 4A, MP 4.41-4.43.

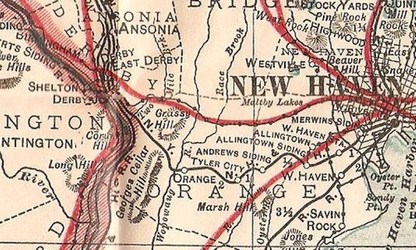

[1.5] This snapshot is from a George F. Cram map dating to between 1902 and 1906. These maps were published and pasted into the rear cover of the Register and Manual issued annually by the Connecticut secretary of the state's office and today called the 'Blue Book' for the current color of the cover. Tyler City is located in the lower center of the map under the N in New Haven. The lines in red are highways. These maps are quite useful for locating geographic features, place names, trolley lines, stations, sidings on railroads, etc.

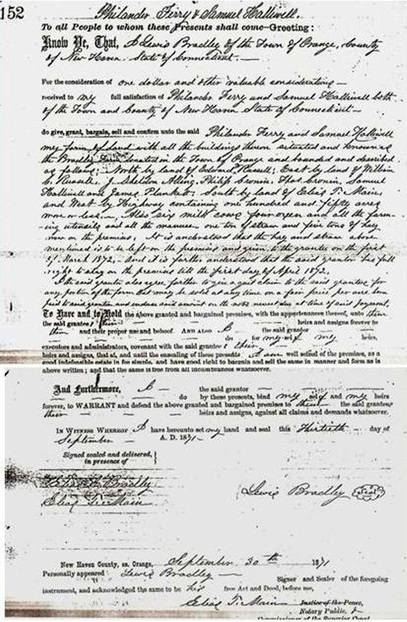

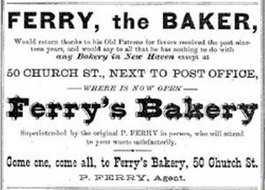

[1.6] Two industrious New Haven 'prospectors,' as Woodruff calls them, conceived the idea of this new suburban metropolis. Samuel Halliwell was the proprietor of the Elm City Tea Store, which, according to the article in the Register, carried nearly a dozen varieties of tea, nine coffees, numerous spices, and wine also. The latter is interesting in terms of the later restriction of the sale of alcohol at the Tyler City general store. Philander Ferry operated a confectionary shop that made and sold baked goods and ice cream.3 These purveyors of sweet-scented delicacies apparently got a whiff of opportunity from the new railroad that ran near their stores. They reportedly took the train several times to search out a suitable site and they settled on Lewis Bradley's 175-acre farm in Orange late in September of 1871.4 Copies of the deeds are valued documents in the OHS collection. The Bradley parcel came with all the buildings, plus "six milk cows, four oxen, and all the farming utensils and all the manure, one ton of straw and five tons of hay" for annual payments starting on April 1, 1872, when Bradley had to leave the premises, and ending on April 1, 1876, totaling $24,400, plus interest and taxes.

Additional parcels north and east of the Bradley farm came from members of the Russell family. A map in the Orange town clerk's office credits the surveying to the eccentric George Beckwith, a colorful character, whose capitalized listing in a New Haven city directory of the period says he was a "surveyor and almanac maker, teacher of mathematics and phonography." According to Woodruff, he was always barefoot, wore a long-tailed coat and a white beaver hat. Copies of his almanac [click here] are in the NHMHS collection. The Register article says Sylvanus Butler was hired first and we do note a Butler St., otherwise unexplained, on the Tyler City map, but if he produced any maps they have not survived. The Courant gives an accurate description of the layout as consisting of eight avenues, which we count as seven north-south, plus New Haven Ave. east-west, serving as 'Main St.' Each was to be 70-ft in width and one mile in length, with equally wide cross streets and most of the lots a uniform 50x150 feet.5 The avenues were cut through what was then part cultivated land and part virgin forest. The work reportedly began on March 14, 1872, and was completed in June, laying out 2,000 lots according to overblown newspaper ads. The total was actually more like 1,000 lots. Howard Treat Sr., retired Orange town clerk, said in a 1972 article that his grandfather was asked by Halliwell to hitch up oxen and plow and back-furrow the pathways in the dirt that would be Tyler City's streets and avenues.6

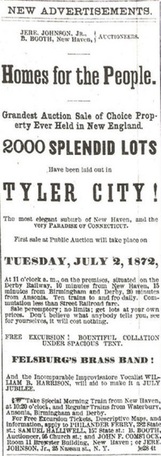

[1.7] The resourceful entrepreneurs were not about to neglect the railroad in their plans. Rather, they sought to entice it into cooperation by naming streets for NH&D officials Harrison, Marble, Quintard, Atwater, and Sperry. Roads were also designated to honor locals Russell and Bradley and themselves. The naming of the envisioned metropolis for Morris Tyler, railroad president [1869-1874] and "energetic lieutenant governor" [1871-1872] was the coupe de grace.7 The well-respected Tyler was in the boot and shoe trade and had also served as mayor of New Haven from 1863 to 1865. The naming after him and the others and the cooperation elsewhere might indicate some closer arrangement between the developers and the railroad but, other than Halliwell owning some NH&D stock in the 1880s, we know of no formal agreements. A well-attended public auction took place on July 2, 1872, complete with the promised entertainment and "bountiful collation" under tent. The Register said the first seven-car train leaving New Haven was full and that it returned to pick up a second trainload of "human freight," perhaps bringing 1,000 potential buyers.8 Other sources claim that still more people went by horse, cart, and foot. The newspapers on July 3 carried the names of 40 people who purchased 86 lots at a going rate of $4 per foot, based apparently on the typical frontage of 50 feet. We have listed their names below.9 The one deed we have seen appears to indicate a sale price of $250 for the standard size lot, yielding a total of $219,000, a figure which probably was augmented by the prices of some of the larger lots.

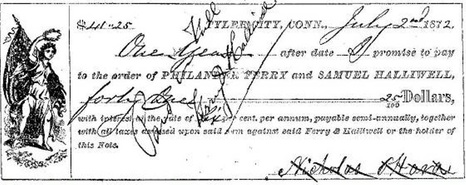

A story that may be apocryphal says that one individual paid $5,000 before the auction for a corner lot next to the site proposed for the town hall. In any case, this was a considerable one-day inflow for the entrepreneurs and more sales would come, perhaps eventually totaling Woodruff's figure of $510,000. The July 2 purchasers bought an average of two lots per person, with as many as seven for one buyer, and six for the lone out-of-state party from New York. Most were buying adjacent lots apparently intending to put a larger piece of property together. The 13 buyers of lesser means bought single lots, probably making large downpayments and financing the rest, as shown with the $40.25 payoff receipt we have posted below. With no zoning restrictions, the customers who bought single lots had the right to live on half a lot and sell or rent the other half. This was then, as advertised, a great opportunity for the common man to buy a plot of land in the country, live well, and prosper. Fine residences were built for Ferry and Halliwell and, though the latter cost $50,000, it was reportedly scaled back from the more lavish, original plans. A later Courant article says that this was merchant-turned-land speculator Halliwell's biggest real estate deal, that he had several partners, and that 25 houses were built to be marketed to prospective buyers. This is the only mention of these particular claims that we have seen thus far.

[1.8] Copy of deed on page 152 of the Orange land records at the town clerk's office. This shows the sale of Lewis Bradley's farm to Samuel Halliwell and Philander Ferry and is dated September 30, 1871. Note the formalized language of "one dollar and other valuable considerations" as the terms of the sale. An additional deed on page 153 shows $24,400 owing to Bradley and spread out over several payments, plus interest and taxes. Much like their customers, Halliwell and Ferry were financing their purchase over time. The Bradley farm here is said to consist of 150 acres "more or less," Perhaps the 33 acres of Russell land was added in to bring the total acreage to 183, which is closer to the 175 acres usually given as the size of the Bradley farm.

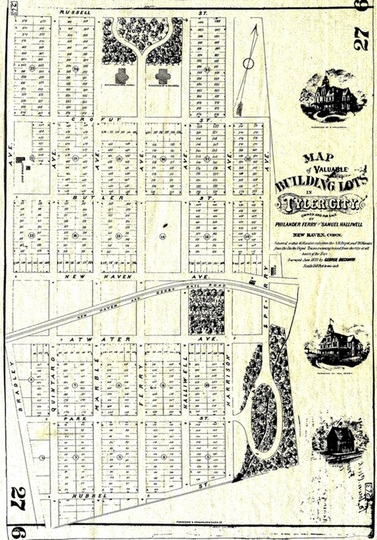

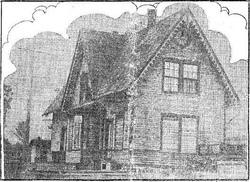

[1.9] Tyler City was nevertheless booming at the start, at least on paper, and the promoters would have a two-story train station built at their own expense and presented to the railroad on condition that trains would always stop here. The Courant reported that a freight depot was "nearly completed" late in 1871 and that a station, "will soon be opened."10 A single building for both freight and passengers is all we are aware of ever being built and it probably was finished by the time trains began to stop there on June 1, 1872.11 Contrary to what Woodruff, and others perhaps following her have said, Tyler City was always a regular stop for at least some trains on the NH&D from 1872 on. A vignette of the Tyler City station is seen at the lower right of this 1872 promotional map. The 'pink' original is in the collection of the Orange Historical Society and was reproduced on page 23 of their History of Orange Sesquicentennial booklet [also now online, click here] in 1972, coincidentally Tyler City's centennial year. Click on the map below to enlarge it and note the 'June 1872' date and Beckwith's name in the credits. Most all the locations discussed are on this map, as well as vignettes of the Ferry and Halliwell mansions and their side-by-side location above Crofut St. in a setting that is called 'Home Park.' The paper reported in 1873 that real estate activity was still "brisk" with many houses going up.12 Perhaps these were the houses mentioned above and part of an effort to boost sales. Later it was reported that Mr. Halliday, undoubtedly meaning Halliwell, "offers a site for an Episcopal church there" and that the first service was on August 7, 1873, probably at his home. It goes on to say it was "hoped that a parish would be built up."13 The fact that Halliwell was opening his own property for church services is an interesting comment on the sobriety and moral tone that the proprietors wanted to set for their new community. It would be seen in their other actions as well.

[1.9] Tyler City was nevertheless booming at the start, at least on paper, and the promoters would have a two-story train station built at their own expense and presented to the railroad on condition that trains would always stop here. The Courant reported that a freight depot was "nearly completed" late in 1871 and that a station, "will soon be opened."10 A single building for both freight and passengers is all we are aware of ever being built and it probably was finished by the time trains began to stop there on June 1, 1872.11 Contrary to what Woodruff, and others perhaps following her have said, Tyler City was always a regular stop for at least some trains on the NH&D from 1872 on. A vignette of the Tyler City station is seen at the lower right of this 1872 promotional map. The 'pink' original is in the collection of the Orange Historical Society and was reproduced on page 23 of their History of Orange Sesquicentennial booklet [also now online, click here] in 1972, coincidentally Tyler City's centennial year. Click on the map below to enlarge it and note the 'June 1872' date and Beckwith's name in the credits. Most all the locations discussed are on this map, as well as vignettes of the Ferry and Halliwell mansions and their side-by-side location above Crofut St. in a setting that is called 'Home Park.' The paper reported in 1873 that real estate activity was still "brisk" with many houses going up.12 Perhaps these were the houses mentioned above and part of an effort to boost sales. Later it was reported that Mr. Halliday, undoubtedly meaning Halliwell, "offers a site for an Episcopal church there" and that the first service was on August 7, 1873, probably at his home. It goes on to say it was "hoped that a parish would be built up."13 The fact that Halliwell was opening his own property for church services is an interesting comment on the sobriety and moral tone that the proprietors wanted to set for their new community. It would be seen in their other actions as well.

[1.10] This is a promissory note for $41.25 issued to Nicholas O'Hara at the July 2 auction, giving him one year to pay off what must have been the balance due on his purchased property. The lot number of the parcel he bought is not specified but O'Hara's name does appear as the purchaser of one lot in the newspaper articles of July 3: see note 9. The counter-signature says: "Paid in Full, Ferry & Halliwell," with neither the date of the payoff shown nor the amount of interest charged at the 6% rate specified. Perhaps those details were on a separate reciept. The scratching out of his name may be an additional indication that he was paid up in full.

[1.11] A copy of the 1872 Tyler City prospectus map. The '263' in the upper left and lower right corners is perhaps a printing-sequence number. We thought that the '27 6' in the upper right and lower left corners might show that this map was issued to the purchaser of lot 6 in block 27 but the blocks do not go beyond 25, and lot 27 is not in block 6 either. The OHS collection includes a large, clean, poster-size copy of this map, with no markings and no vignettes of the buildings, as well as two cloth-backed copies of similar size, one of which has numerous X and O markings and the names of the lot purchasers penciled in. Neither of the cloth copies, which are being suitably encased for preservation, have the identifying numbers seen here but they do have the vignettes. The station image, apparently thought attractive enough to be reproduced separately, is from the lower right of the prospectus map. We completely agree with that and note that this idealized view of the planned station was, understandably, not exactly the way it was built. The appearance of this station has always struck us as looking more like a Victorian home than a depot per se, probably done deliberately as part of the residential ambience the promoters were looking to create here.

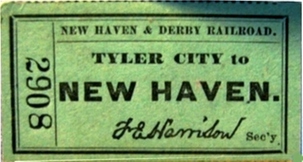

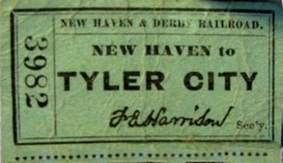

[1.11.1] These two ticket images were found recently. Blank on the reverse side, they probably date to the 1880s. Harrison was secretary from 1867 to 1886.

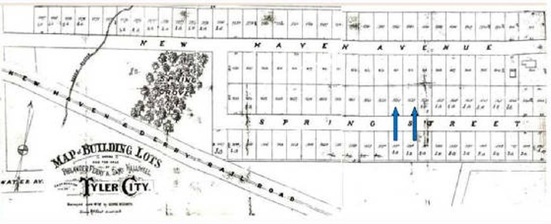

[1.12] While we have not yet been able to determine the population in its early days, a check of the 1930 census records shows 66 residents in Tyler City in its later years. There was a call in 1874 for an earlier train into New Haven for the mechanics and "workmen" who were living here at the time. In that same year Elm City Postmaster Nehemiah Day Sperry, who was also an NH&D director, successfully petitioned Washington to establish a Tyler City post office, a move that was tantamount to federal recognition of the locale. NH&D trains had started carrying the mails by government contract on November 1, 1871, part its mission of improving communication with the Naugatuck Valley. The entire town of Orange then went to daily "railroad mail" from the earlier "thrice-weekly butcher's wagon mail service."14 With easily affordable housing as well as rail and postal service, the newspaper said that Tyler City residents "will be in a fair way of living, enjoying and advancing equally with their neighbors."15 Victoria Grove, which we will talk more of further on, served as an amenity as well as a marketing tool, with use of the swings, tables, and the "culinary department" free to all in 1874. It is seen on the map adjacent to the station. A larger Lincoln Park, named after the recently slain president, sits to the southeast, with Trout Brook, idyllically rechristened Sylvan or Silver Brook, running through it. The map below shows the eastern portion of Tyler City with lots along each side of both New Haven Ave. and Spring St. The latter street was built at this time and so-named as leading to Spring Grove and to Nectar Spring in the center of the park oval. Here Nature's simplest and purest refreshment could be had in what was, after all, practically the Garden of Eden, the "very paradise of Connecticut." The blue arrows mark the two lots, discussed below, that were donated by Halliwell and Ferry for the Tyler City schoolhouse.

[1.13] This map shows the lesser-known part of Tyler City, east of the railroad station along New Haven Ave. and Spring St. The blue arrows mark the two lots, discussed below, that were donated by Halliwell and Ferry for the Tyler City schoolhouse that opened in 1874. The copy of this map that is in the Orange town clerk's office has pencilled-in names corresponding to the purchasers of lots at the July 2, 1872 auction. While Sylvanus Butler may have done some of the early surveying, none of his Tyler City work seems to have survived. The two Beckwith maps have become the official record with the property deeds even today referencing the lot numbers on these maps. The town clerk's offices have the land records, in West Haven for years prior to 1921 and years thereafter in Orange.

[1.14] Aerial view in 1934 of the Tyler City area. The railroad station would stand for about two more years until the fire of July 4, 1936, its cross-gabled roofline noticeable from the air. The general store, today with an address of 80 New Haven Ave., is seen to the right and across the street. Sylvan, aka Silver, Brook meanders through the remains of Spring Grove on the right. Tyler City is unpopulated otherwise, except for one or two homes and the Halliwell mansion, out of sight to the north. Note how Harrison Ave., just west of the depot, continues south across the railroad track into what was once Victoria Grove. This road, along with several other erstwhile thoroughfares, has disappeared. Also visible here is the is the foundation of the Tyler City factory building, diagonally northwest of the station. See below at MP 1.23.

[1.15] Tyler City Rd. still leads today from the center of Orange to Racebrook Rd., just north of Russell Ave., which was the northern border of the envisioned town. This link should take you to the area as it is now. New Haven Ave. was newly laid out in 1872 through the center of the fledgling town and so-named for the big city to the east that could now be easily be reached by train. According to the 1872 map, the railroad station was to stand north of the track, right on New Haven Ave., east of Halliwell Ave. between Harrison and Sperry Aves. A Price and Lee map in the 1927 Milford-Orange city directory shows no Harrison or Sperry Ave. and nothing below New Haven Ave. in existence at that time. Apparently, the only part of Tyler City that was fully 'laid out' and with streets built was enclosed by Racebrook Rd. (Bradley Ave. on the 1872 map), Russell St., and Halliwell and New Haven Aves. The 1872 map shows that a general store was going to be located northeast of the station and the aerial shot shows it there. One Charles H. Amesbury moved from Norwich to take up residence here at this time. It is not known whether he was connected with the proprietors in some way, or he answered an ad, or just thought that this was a good business opportunity but he signed a purchase agreement with Halliwell and Ferry on May 28, 1872 for the land on which he was to build and operate the store. He also agreed therein to the repeated stipulation that he not sell alcoholic beverages. Woodruff says Amesbury was the postmaster as well, likely Tyler City's first, starting in 1874. The restriction on alcohol sales is interesting. While not making this community dry per se, it certainly set a conservative, even religious, tone that was undoubtedly intended to keep up property sales by barring the wrong sort from 'paradise.' The white house that stands today on the north side of New Haven Ave., with the antique windows on the uppermost level, has been verified by the family that once lived there as the former grocery store and post office.

[1.15] Tyler City Rd. still leads today from the center of Orange to Racebrook Rd., just north of Russell Ave., which was the northern border of the envisioned town. This link should take you to the area as it is now. New Haven Ave. was newly laid out in 1872 through the center of the fledgling town and so-named for the big city to the east that could now be easily be reached by train. According to the 1872 map, the railroad station was to stand north of the track, right on New Haven Ave., east of Halliwell Ave. between Harrison and Sperry Aves. A Price and Lee map in the 1927 Milford-Orange city directory shows no Harrison or Sperry Ave. and nothing below New Haven Ave. in existence at that time. Apparently, the only part of Tyler City that was fully 'laid out' and with streets built was enclosed by Racebrook Rd. (Bradley Ave. on the 1872 map), Russell St., and Halliwell and New Haven Aves. The 1872 map shows that a general store was going to be located northeast of the station and the aerial shot shows it there. One Charles H. Amesbury moved from Norwich to take up residence here at this time. It is not known whether he was connected with the proprietors in some way, or he answered an ad, or just thought that this was a good business opportunity but he signed a purchase agreement with Halliwell and Ferry on May 28, 1872 for the land on which he was to build and operate the store. He also agreed therein to the repeated stipulation that he not sell alcoholic beverages. Woodruff says Amesbury was the postmaster as well, likely Tyler City's first, starting in 1874. The restriction on alcohol sales is interesting. While not making this community dry per se, it certainly set a conservative, even religious, tone that was undoubtedly intended to keep up property sales by barring the wrong sort from 'paradise.' The white house that stands today on the north side of New Haven Ave., with the antique windows on the uppermost level, has been verified by the family that once lived there as the former grocery store and post office.

[1.16] What is not too well known about this idyllic settlement in the woods and Victoria Grove in particular, is that, in addition to it being a popular excursion destination, it became something of a liberal soapbox and rallying point for 'subversives.' While mainstream engagements included governors, mayors, and the clergy, the iconoclastic George Beckwith was a popular speaker here. In 1888 Fred Siebold, an Elm City "anarchist agitator" moved his family to Tyler City and opened a saloon nearby, probably on Milford Tpke., where his like-minded associates "congregate on Sundays, and, while destroying many kegs of beer, discuss measures for the equal distribution of wealth." There are several mentions of Siebold in the Register, which always paints him as a radical supporter of the labor movement, in company with the likes of John Most, Emma Goldman, and the Haymarket massacre victims [click here].16 Undoubtedly the most historic event that would take place in Tyler City came in 1890, when the Courant reported that a "colored" church camp meeting, dubbed the "Ten Days Jubilee in the Wilderness," was to be held here. This would be no ordinary gathering. The sponsoring group was the Haven Memorial Church, pastor J. Sanford Ray, which was then meeting in Day's Hall at the corner of Broadway and York St. in the Elm City. This was reportedly "the only colored congregation in the New York East Methodist Episcopal Conference." While part of the purpose was to raise funds to purchase a site for their own place of worship, what was really up for consideration was support for a Republican Party effort, spearheaded by Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, for a law to provide federal oversight of Congressional elections in the post-Reconstruction South. Speakers came from as far away as Ohio, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. Among them was Timothy Thomas Fortune [click here]. Born a slave in Florida, Fortune had been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, and is credited with coining the term 'Afro-American.' He founded the New York Age, "the most brilliant Negro newspaper in the world" and would give his famed address on liberty here at Tyler City. Reports numbered the attendance that included many women and children at 1,000 and 1,200 on some days and it was said that the "coloreds" were outnumbered by whites who were urged to support the cause. The crowds were so enthusiastic that the encampment was extended for three more days. Other fraternal associations like the Masons and the Odd Fellows were invited to attend the church services and Biblical expositions that dominated the meeting. The event ran from July 28 to August 7 and a figure of 10,000 total attendees would not be unrealistic.17

[1.17] The following resolution, introduced by Rev. Albert P. Miller of New York, was passed unanimously on July 31. The newspapers ran it the next day, reading "We Afro-American citizens of the state of Connecticut, being convinced that the condition of affairs is such that a uniform election law is necessary to insure a fair and just expression of the public will in federal elections, do endorse the Lodge federal election bill, passed by the house of representatives, and now pending before your honorable body, and do earnestly petition hereby that your august body concur in the action of the house of representatives."18 Emotions boiled over the issue but hopes were high for a favorable outcome. The culmination of the Jubilee was to be an address by the Rev. Mrs. Phebe Hanaford [click here], who in 1868 had become the first woman minister to be ordained in New England.19 She was a popular preacher, a prolific writer, a Universalist pastor, and an outspoken advocate of abolitionism, temperance, suffragism, and equal rights for blacks, women, and the working man, causes that often coalesced in the social conscience of the day and here at the Tyler City meeting. Hanaford had held her own on the podium many times with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony and her death in 1921 at age 92 made headlines across the country.20 The article that said she would be speaking "on the same spot where she preached seventeen years ago" to an earlier camp meeting showed that by 1890 Tyler City had a nearly a 20-year tradition of religious, political, and social activism. While not exactly an agent of anarchy, the Derby road was advertised in newspapers and brochures as providing the frequent service that undoubtedly made this dissident activity more possible. It likely brought Fortune, Hanaford, the other speakers, and the huge crowds here to make history at Tyler City. Controversy over the Lodge bill would continue until January of the next year. The Palladium, New Haven's liberal newspaper, wrote a sober editorial supporting the bill, which it claimed did not threaten states' rights at all, and said that the Democratic governor of Ohio had spoken "with the loud voice of an ass" when he declared that any effort to enforce the federal elections law in his state would be resisted by "all the armed powers at this command." Unfortunately, Southern Democrats and conservative newspapers like the Register would defeat this early attempt at civil rights legislation by a single vote in the Senate [click here].21 Economic reprisals against the North had been threatened, federal interventionism was decried, and some argued that even many blacks thought the proposal was not a good idea. This largely unknown, early battle in the national civil rights movement is a notable chapter in Orange's history and seems worthy of commemoration, celebration, and additional research.

[1.17.1] The upper arrow shows the Tyler City schoolhouse, as the Chapel of the Good Shepherd sitting below New Haven Ave. and above Spring St. The bell tower has been moved at least once and probably is not the original. The schoolhouse building committee was authorized to "expend a sum not to exceed Forty Dollars to erect a suitable Cupola or Bell Tower" to be placed "at an equal distance from front to rear end" [p20]. As seen here, it is on the north end of the structure over the sanctuary addition and, in the 1945 and present-day photos below, the tower is toward the south end of the building. The small structure above and to the right of the chapel was probably the shed, built in 1911 to accomodate eight teams of horses during services, according to data given on page 31 of the Orange sesquicentennial history [click here] and brought to our attention recently by Ginny Reinhard at OHS. Directly to the right of the chapel, we have just noticed that the parish hall building, now being used as the rectory, seems to be standing in the 1934 shot. The lower arrow points to the railroad crossing at Dogburn Lane.

[1.17.2] This photograph appeared in a 1945 publication entitled Historical Notes About Christ Church, West Haven, Connecticut, Concerning Its Two Hundred Years of Existence, 1723-1923. In a section [p96ff] about the creation of the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, it says that the school building was consecrated as the chapel on April 19, 1913 by Episcopal Bishop Chauncey Bunce Brewster [click here]. The donation of land by Ferry and Halliwell was acknowledged, as was the deeding of the property to the church after the school closed in 1909. According to the book, the cross was removed from the steeple of the Episcopal Church in Stratford, the oldest in the Connecticut diocese, and set on the chapel here.

[1.18] The 1874 Tyler City schoolhouse at 378 Spring St., now the home of Our Lady of Sorrows Church, where the traditional Latin Mass is still celebrated instead of the mainstream Roman Catholic liturgy. The structure has had a long ecclesiastical history since it was decommissioned as a school in 1909.

[1.19] While Halliwell and Ferry were wary of Demon Rum and tried to keep alcohol out of Tyler City, they were also determined to make sure that education was a part of life here. A school district, Orange's fifth, was organized on November 3, 1873. Classes were first held in one of the waiting rooms at the railroad station until a facility was built on land donated by the proprietors. According to district records in the OHS collection, April 15, 1874 was the expected completion date [p16] and building lots 1634 and 1635 were given as the site [p4]. See the blue arrows on the map above at MP 1.13. By May 23, the school district had moved its meetings from the railroad station to the new schoolhouse [p21]. Woodruff says that classes opened on September 1, 1874 in "the new schoolhouse just completed" [p102] and that, when district schools were eliminated in 1909, the building passed to Christ Church, West Haven [p140]. It seems to have already been the site of Sunday school services and prayer meetings then, a religious use that was specifically permitted in the deed to the property and reflected the proprietors' moralistic tone. Increased participation persuaded Jane Halliwell, Samuel's widow, to pay a sum of money to the town of Orange to take back the land given for the school and deed it to the church. The two lots behind the school property were donated by Miss Susan V. Hotchkiss, resulting in a four-parcel tract stretching from New Haven Ave. to Spring St. The building was remodeled to give it a church-like interior, simple stained-glass windows, and a sanctuary area on the north end. The altar was donated by St. Paul's Church, New Haven and the bell tower was the gift of the Sunday school children and Christ Church parishioners. The chapel went thereafter to the New Haven branch of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints on January 20, 1959, which kept it until ca. 2000. Today the building at 378 Spring St. has been Our Lady of Sorrows Church since about 2004. Harking back to dissident elements in Tyler City's past, the current congregation worships with the Latin Mass, which has been a counter-culture movement in the Roman Catholic church since the 1960s.

[1.20] Education as a hallmark of Tyler City would also see other endeavors. The Ferry mansion would be left later for a short-lived attempt as a girl's boarding school. A large residence at the corner of Ferry Ave. and Crofut St., built by Edwin Robbins, whose name coincidentally corresponds to the chief clerk for the NH&D from 1884-1887 [see Track 3, MP 3.6.2] and possibly a later legal representative for the NYNH&H, would become Altworth Hall, a prep school, around 1878. Though it soon failed, a few years later the house was rented as the first location of the New Haven County Temporary Home for Dependent and Neglected Children, which opened on January 1, 1884. The first of the 'inmates,' as they were then styled, was William Mooney, a 7-year-old from Cheshire, who arrived shortly thereafter.22 Almost immediately controversy arose, precisely over education. The town refused to accept the home's children into the school system, citing a lack of space and their non-resident status, even flouting the expressed opinion of Governor Waller.23 According to Woodruff, when the town later refused a request to build sidewalks to the railroad station, the home moved to New Haven. It was more likely the schooling issue itself, rather than the sidewalks, that caused the home to depart, but other sources say the reasons were the want for a more permanent location and also possibly charges of mismanagement and anti-Catholic 'proselytizing' there, the latter charges later examined and dropped.24 The move was certainly not for lack of public generosity. A Register article entitled "Please Stop It" said that 50 gifts had been collected for the 27 children living there and no more were needed.25 On July 1, 1886, the home reopened in the Elm City on property the county purchased at Shelton Ave. and Bassett St.,26 and ultimately in 1909 it moved to its own newly constructed buildings in the Allingtown section of West Haven, then still a part of the town of Orange. Those structures and that site are today occupied by the University of New Haven. Some of the interesting history of this facility is addressed on Track 8.

[1.20] Education as a hallmark of Tyler City would also see other endeavors. The Ferry mansion would be left later for a short-lived attempt as a girl's boarding school. A large residence at the corner of Ferry Ave. and Crofut St., built by Edwin Robbins, whose name coincidentally corresponds to the chief clerk for the NH&D from 1884-1887 [see Track 3, MP 3.6.2] and possibly a later legal representative for the NYNH&H, would become Altworth Hall, a prep school, around 1878. Though it soon failed, a few years later the house was rented as the first location of the New Haven County Temporary Home for Dependent and Neglected Children, which opened on January 1, 1884. The first of the 'inmates,' as they were then styled, was William Mooney, a 7-year-old from Cheshire, who arrived shortly thereafter.22 Almost immediately controversy arose, precisely over education. The town refused to accept the home's children into the school system, citing a lack of space and their non-resident status, even flouting the expressed opinion of Governor Waller.23 According to Woodruff, when the town later refused a request to build sidewalks to the railroad station, the home moved to New Haven. It was more likely the schooling issue itself, rather than the sidewalks, that caused the home to depart, but other sources say the reasons were the want for a more permanent location and also possibly charges of mismanagement and anti-Catholic 'proselytizing' there, the latter charges later examined and dropped.24 The move was certainly not for lack of public generosity. A Register article entitled "Please Stop It" said that 50 gifts had been collected for the 27 children living there and no more were needed.25 On July 1, 1886, the home reopened in the Elm City on property the county purchased at Shelton Ave. and Bassett St.,26 and ultimately in 1909 it moved to its own newly constructed buildings in the Allingtown section of West Haven, then still a part of the town of Orange. Those structures and that site are today occupied by the University of New Haven. Some of the interesting history of this facility is addressed on Track 8.

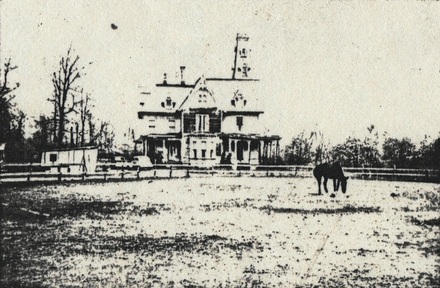

[1.21] The montage at top pictures show Halliwell's grand Victorian mansion at Tyler City, Mr. Samuel Halliwell seemingly at an early age, and the ruins of the Ferry mansion after the girls' academy failed and by the time the accompanying article was published in 1929 [NHSR/10/27/1929/03]. The Halliwell structure went on to become the home of the Orange Hunt Club and later the Orange Riding Stables. As is seen in the middle shot, the mansion is in its last days ca. 1950 when it was owned by the Tompkins family and still being operated as a riding stable. Property rights to the old NH&D line from the Tyler City station site, eastward as far as Campbell Ave. in West Haven, have been found in deeds as also belonging to the family. The bottom photo appeared in the aftermath of a 6/22/1953 fire reported the next day in a New Haven paper. The article was entitled "3 FIRES RAVAGE 80-YEAR-OLD ORANGE 'HOTEL.'" The 15-room structure is described as having been built some 80 years ago for use in "a 'dream city' which never materialized." Since two men were seen running from the blaze, it was branded as arson, with three separate fires set in the building. The Berner Lohne Co., Woodbridge contractors, owned the structure at the time and it was being demolished to clear the land for a housing development. In advance of that, Fire Chief Chris Winkle said that a large family, probably the Tompkins, had moved out just a month ago. The article makes it sound like Halliwell moved in only after the Tyler City hotel idea, which we have never heard of before, faded with the rest of the dream city. Further speculation aside, the article at least pinpoints 1953 as the demise date for the home of Tyler City's other proprietor.

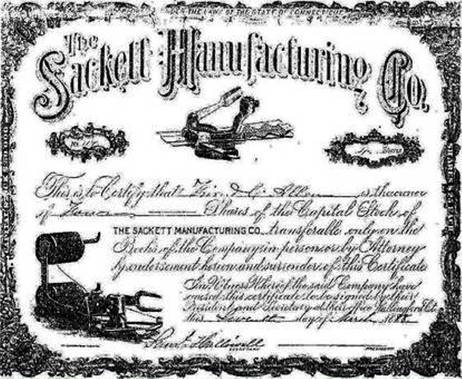

[1.22] While this would never become the destination its promoters foresaw, there was economic activity here, though seemingly laced with some Tyler City intrigue. The Courant says that a shop for the manufacture of looms was being talked of in 1877 but we hear nothing more of it.27 The first industrial operation we know of was the Sackett Mfg. Co. While Woodruff says this came in 1871, we find that it was vacating space in Wallingford in 1887 and planning to move to Tyler City then, apparently through Halliwell's doing.28 Now described as "an old and supposedly wealthy business man" with an office at 80 Church St. in New Haven, he was said to have built a brick factory here worth $25,000, with electric lights and all the modern improvements, he and his wife in control of most of the stock.29 Interestingly, he was also accused of embezzlement and taking money under false pretenses at this time in matters seemingly unrelated to Tyler City. It was necessary for long-time associate Philander Ferry to bail him out twice before the charges were nolled and an out-of-court settlement was made. Sackett Mfg., perhaps needed for its sewing-machine manufacturing machinery, then appears to have morphed into the Peerless Buttonhole Attachment Co. [click here]. Woodruff says the operating partners were J. Willis Downes of New Haven and the same William Chauncey Russell [click here] who sold some of the land for Tyler City, now said to be of the Russell Bros. 'firm,'30 with Downes acting as treasurer for the new company. One device was patented [click here], but to a Louis Bullet. J.W. Downes makes his first appearance in another Register article with fellow attorney Charles A. Harrison, both of whom were appointed on behalf of the Wallingford stockholders to investigate the bankruptcy of the Sackett operation.31 The company's directors, not named in the newspaper, had attempted to ward off the investigation by having a receiver appointed, an action that was vacated by Judge Andrews at Harrison's request and Sackett's Pres. Terry initially even refused to have the books examined until he allowed it through his attorney.32

[1.22] While this would never become the destination its promoters foresaw, there was economic activity here, though seemingly laced with some Tyler City intrigue. The Courant says that a shop for the manufacture of looms was being talked of in 1877 but we hear nothing more of it.27 The first industrial operation we know of was the Sackett Mfg. Co. While Woodruff says this came in 1871, we find that it was vacating space in Wallingford in 1887 and planning to move to Tyler City then, apparently through Halliwell's doing.28 Now described as "an old and supposedly wealthy business man" with an office at 80 Church St. in New Haven, he was said to have built a brick factory here worth $25,000, with electric lights and all the modern improvements, he and his wife in control of most of the stock.29 Interestingly, he was also accused of embezzlement and taking money under false pretenses at this time in matters seemingly unrelated to Tyler City. It was necessary for long-time associate Philander Ferry to bail him out twice before the charges were nolled and an out-of-court settlement was made. Sackett Mfg., perhaps needed for its sewing-machine manufacturing machinery, then appears to have morphed into the Peerless Buttonhole Attachment Co. [click here]. Woodruff says the operating partners were J. Willis Downes of New Haven and the same William Chauncey Russell [click here] who sold some of the land for Tyler City, now said to be of the Russell Bros. 'firm,'30 with Downes acting as treasurer for the new company. One device was patented [click here], but to a Louis Bullet. J.W. Downes makes his first appearance in another Register article with fellow attorney Charles A. Harrison, both of whom were appointed on behalf of the Wallingford stockholders to investigate the bankruptcy of the Sackett operation.31 The company's directors, not named in the newspaper, had attempted to ward off the investigation by having a receiver appointed, an action that was vacated by Judge Andrews at Harrison's request and Sackett's Pres. Terry initially even refused to have the books examined until he allowed it through his attorney.32

[1.23] The top item was found accompanying a newspaper article [NHR//NHJC/03/14/1964/08; NL18.6.8] and duplicates the photo posted at MP 1.0, with the important exception that the Tyler City factory building, as noted in the caption, has not been cropped out here. Its location has been a matter of speculation for more than a half century. Here it is finally revealed as a two-story structure on the northwest corner of Harrison and New Haven Aves., conveniently adjacent to the railroad station and freight platform. NH&D Pres. Stevenson mentions that the factory is being built in 1887 as part of the economic development and opportunities for "working men and women" that his railroad was bringing to the New Haven area [NHER/08/09/1887/01]. This would become the home of the Sackett Mfg. Co., which relocated here in 1888, around the time we think this photo was taken. Four shares of Sackett stock were purchased by Friend(?) C. Allen on March 7, 1888 and certificate no. 117, seen here, shows the company still in Wallingford. The certificate is signed by Secretary Halliwell but not yet endorsed by President Terry. The left margin shows that $50,000 was the amount of capital stock issued. By February 1889, Sackett was in bankruptcy but the factory was used by successor companies until it burned in 1898.

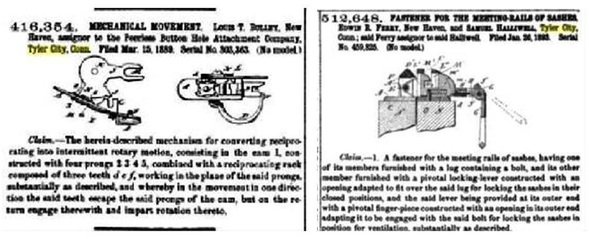

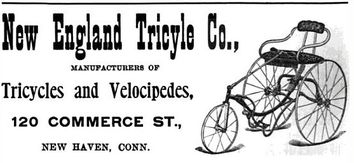

[1.24] As if there were not already enough millinery intrigue, Hiram B. Brower of Tyler City and B.O. Pratt of Middletown were co-grantees in 1890 of patents for embroidery and hemming attachments for sewing machines.33 Perhaps they intended to associate themselves with Peerless, which appears to have lasted at least until early 1893.34 The basement of the factory was occupied later by a creamery run by Edward W. Russell, E.C.'s brother, a gentleman farmer and prize winner at the Orange Agricultural Fair. He made butter that he sold locally, both wholesale and retail, in an operation that was said to have dated back to 1852. The last venture to use the factory was the New England Tricycle Co., which set up shop here in 1897 and, according to Woodruff, manufactured baby carriages as well. Other local industrial ventures included window-sash fasteners, patented in 1893 to Halliwell and an Edwin Ferry, perhaps a relation of Philander, [click here] and the production of plaster-of-Paris ceiling decorations, some of which were used in the Halliwell and Ferry mansions. Neither of these gambits seemed to amount to anything substantial, though the latter reportedly got as far as the foundation for a building. Tyler City's industrial fame, minimal as it was, ended when its only factory building burned on October 28, 1898 and the tricycle company relocated to New Haven.35 The owner at the time was given as J. Willis Downes, who was also said to be "a member of the firm." The factory then was reportedly worth $5,000, covered by insurance, with damage to the machinery said to be around $6,000.36 The company took up quarters in the Clarke Bldg. at 120 Commerce St. and was said to employ 50 hands, a fair number of people presumably to have been working at Tyler City previously.37 The ad, below, appears on page 995 in the Price & Lee New Haven city directory for 1899 [click here]. Downs (sic) and a Mr. Whitmore are listed as the proprietors on page 478.

[1.24] As if there were not already enough millinery intrigue, Hiram B. Brower of Tyler City and B.O. Pratt of Middletown were co-grantees in 1890 of patents for embroidery and hemming attachments for sewing machines.33 Perhaps they intended to associate themselves with Peerless, which appears to have lasted at least until early 1893.34 The basement of the factory was occupied later by a creamery run by Edward W. Russell, E.C.'s brother, a gentleman farmer and prize winner at the Orange Agricultural Fair. He made butter that he sold locally, both wholesale and retail, in an operation that was said to have dated back to 1852. The last venture to use the factory was the New England Tricycle Co., which set up shop here in 1897 and, according to Woodruff, manufactured baby carriages as well. Other local industrial ventures included window-sash fasteners, patented in 1893 to Halliwell and an Edwin Ferry, perhaps a relation of Philander, [click here] and the production of plaster-of-Paris ceiling decorations, some of which were used in the Halliwell and Ferry mansions. Neither of these gambits seemed to amount to anything substantial, though the latter reportedly got as far as the foundation for a building. Tyler City's industrial fame, minimal as it was, ended when its only factory building burned on October 28, 1898 and the tricycle company relocated to New Haven.35 The owner at the time was given as J. Willis Downes, who was also said to be "a member of the firm." The factory then was reportedly worth $5,000, covered by insurance, with damage to the machinery said to be around $6,000.36 The company took up quarters in the Clarke Bldg. at 120 Commerce St. and was said to employ 50 hands, a fair number of people presumably to have been working at Tyler City previously.37 The ad, below, appears on page 995 in the Price & Lee New Haven city directory for 1899 [click here]. Downs (sic) and a Mr. Whitmore are listed as the proprietors on page 478.

[1.25] In spite of the initial interest, the growth of the new 'city' stalled. Howard Treat, Sr. attributed this to the lack of provision for a public water supply - residents had to dig their own wells in days before drills - and, conversely, to drainage problems and possibly to the "isolation" felt here. The economic slowdown in the Panic of 1873 may have been a bigger factor. In 1877 scheduled stops were reduced to a morning train to New Haven and an afternoon train to Ansonia, with others flagged down as needed, but an 1881 timetable [see Track 2, MP 2.4.1] and ones thereafter show most all trains were stopping here again.38 Nevertheless, defaulting buyers reneged on their lots and by 1882 it was said that most of the houses were "rotting." With properties reverting back to the entrepreneurs, Ferry seems to have sold out his interest completely to Halliwell and quit Tyler City to go back to New Haven. Halliwell died at his residence on March 13, 1898, survived by his widow Jane, who passed away on November 26, 1922.39 The bulk of the property below New Haven Ave. later went from Jane Halliwell's estate as a single parcel ultimately to the current owner, the Orange Hills Country Club. The club's website [click here] has some of the details. The Register article says in 1929 that the Ferry mansion, left for use as an academy for young girls, had failed and the "crumbling remains" of the house were "deep in moss and creeping vines." The entire Home Park tract bounded by Marble, Russell, Halliwell and Crofut Sts., as well as the other forfeited lots, passed to a Margaret G. Coffey, who leased it all to Irwin P. Wener on October 4, 1929 "for a riding academy." Having survived a fire, the Halliwell mansion became the club house of the newly formed Orange Hunt Club.40 Woodruff corroborates this and says the Orange Riding Stables had it thereafter, as well as use of the NH&D right of way as its bridle trail. A longing for home brought Lewis Bradley to repurchase some of his property in his later years. His farmhouse, dating to the late 1700s, was left untouched by the developers and still stands today on Racebrook Rd. Telephone books for the late 1930s show a total of six residences in Tyler City with phone service at that time. The post office lasted until 1916. While the exact dates are difficult to determine, postmasters over the years were Charles Amesbury, 1874; L.A. Schafuit (Schafrit?), 1887; Arthur W. Bowman, 1893 (he was also railroad station agent); John C. Merwin, 1894; Charles Von Benschotein, 1895; and, Charles B. Wells, 1911 (also station agent. Again vacant in 1915, the position was apparently filled by a woman who resigned less than a year later, whereupon it was said that "unless a successor is speedily secured," the location would close and patrons would get "rural service" from the Orange post office.41 Apparently no successor was found and this was the end of the line for the Tyler City post office.42 According to a NYNH&H employee timetable, which we think dates to 1919, Tyler City is still shown as station no. 905, with C.B. Wells as probably the last agent. The Register article said in 1929 that the depot had been maintained by the railroad until recently and "now furnishes a roost for birds." The building lasted until the fire of July 4, 1936. [rev090515]

[1.26] There are many additional notes to be made in Tyler City's surprisingly colorful history. In 1883 Thomas Callahan, a prisoner being transported from Waterbury to county jail in New Haven, jumped off the train here and had to be recaptured; in 1884 Alexander Berry, a boy at the county home with "bow legs" had them successfully broken for straightening at a New Haven hospital; in 1885 the F.S. Andrew & Co. tallow factory burned, probably by arson, and the cattle were saved by an NH&D freight train blowing its whistle [see Andrews siding on the Cram map above]; in 1886 NH&D engineer Tom Quinn made the fastest run on record, 16.5 minutes, with the 7:11 p.m. train from Ansonia to New Haven even stopping at Derby, Orange, and Tyler City [see Quinn on Track 3, MP 3.6.2., Track 4A, MP 4.17, 4.18]; in 1889 a construction extra from New Haven rammed the rear of a stopped train, telescoping a passenger car but not injuring anyone seriously; in 1892 a locomotive "stole" a baseball from a trackside game and the crew tossed it back on the return trip from Ansonia; in 1895 the body was found of a Mr. Vetterman of New Haven who had hung himself in the woods about a mile from the depot; in 1895 Alphonso Pepe, an Italian married man, eloped with a married Italian woman from New Haven with the unlikely name of Marie Antoinette Dotalia; also in 1897, Mr. John Beck set out for the Klondike gold rush, sailing from Belle Dock on the pilotboat Thomas S. Negus; in 1898 a gasoline-powered railroad inspection car made a trial trip from New Haven to Tyler City in 20 minutes; in 1903 a horse named 'Tyler City' crashed through the fence at the Orange Fair races; in 1912 U.S. Army maneuvers saw the Reds marching through the area in pursuit of the Blues; and in 1919, sadly, Edgar H. Edwards, one of the NYNH&H's "most trusted" engineers" was apparently struck in the head while leaning out of the cab east of Tyler City and died of his injuries.43

[1.27] Two of the patents listed in the USPTO's Official Gazette with Tyler City as the location.

[1.28.1] The original of this cute 'penny' postcard was found recently in the OHS collection and the photocopy that was here previously was removed. The postmark now is actually quite readable and seems to say August 20, 1915. The card appears to be a novelty item on which the purchaser could have a favorite locale, here Tyler City, stamped in the satchel as a desirable place to visit. The addressee, Antoinette (Nettie) Razee, lived on Old Tavern Road, where regular postal service was likely available, while the sender probably used the rural free delivery indicated by the 'RFD' on the card. The letters GFS stand for Girls Friendly Society, a service organization of the Episcopal Church. The meeting place was the home of the Scharff family, active both in civic and religious affairs. They were among the successful petitioners to the PUC [Docket 1575] for a warning bell at Alling's crossing that was installed by the NYNH&H on 7/31/1915. The meeting here probably had to do with the newly formed Church of the Good Shepherd in the old Tyler City school house. The 'AWCS' may consist of AW as the sender's initials and CS for corresponding secretary, but that is largely conjecture on our part.

[1.29] Notes

1. History of Orange, North Milford, Connecticut, 1639-1949, p. 101-103. Mary Woodruff was born on November 3, 1876 and died on February 18, 1973, at the age of 96. While there may be a few minor errors in her book, she is certainly a primary source, and, in fact, our only source for much of what she wrote about during her lifetime. Would that she had left even more detail of what she lived through.

2. NHSR/10/27/1929/03; ES/11/01/1929/13

3. In the ads and other primary sources, both businesses are said to be on State St., though the street numbers vary.

4. NHDP/10/30/1871/02 gives Halliwell's first name incorrectly as William and also says the property had been purchased prior to October 31. NHJC/10/30/1871/02 says Halliwell and Ferry have purchased the Bradley farm. See listings in Greenough, Jones & Co's New Directory... of the City of New Haven (1874): 102, 121 [click here] and other city directories. This directory says that Ferry lives in Tyler City and that Halliwell is in real estate, with a home address of 37 Davenport Ave. A newspaper article says he was a well-known tea wholesaler in 1871, apparently before he began his real estate career [NHJC/11/20/1871/02].

5. HDC/11/21/1871/04

6. As quoted in Roby Raymond, "Tyler City Tycoons," Connecticut Magazine, July, 1972

7. NHER/11/16/1871/02

8. NHER/03/09/1872/??; NHDP/07/02/1872/01

9. Woodruff says that the auction was July 10. Perhaps the source she was using gave a tally of sales at the end of week starting on July 2. The Register article says there were "several gala days" in the flurry of buying. NHER/07/03/1872/02 and NHJC/07/03//1872/02 both give the same list of names and numbers of lots purchased: James Cusick, four; James Lord, five; J.H. Winfield, one; Charles S. Pratt, one; T.N. Tuttle, two; Nathan Dalzell, two; J.L. Moore, one; Thomas Bright, one; James Taylor, two; Florence Welhauser, two; Christian Meyer, two; Mrs. Beecher, four; Charles Reiul, two; Professor Turner, two; A.H. Cornwall, two; Barbara Saunders, seven; William Lindley, three; James L. Townsend, four; Horace Hubbell, four; W.G. Hooker, two; T.H. Fagan, two; N. Cohen, one; Charles Hildebrand, two; E.B. Stevens, two; Martin Tuttle, one; John F. Comstock, one; George Beckwith [the surveyor], three; William Witchler, one; Nicholas O'Hara, one; G.A. Huntoon, one; L. Schulke, one; W.H. Hazel, one; Charles Horsman, two; James Taylor, two; C.E. Burwell, two; W.H. Kenyon, two; William McWeeney, two; Joseph Colton, one; S. Cohen, one; B.F. Thomas, New York, six. We have the sale deed delivering lots 496 and 498 for "one dollar and other valuable considerations" to E. Charles Hildebrand. The 50-cent amount of the U. S. Internal Revenue stamps to be affixed indicate a sales price of $500 for the two lots, giving a price of $250 each. On the Bradley farm sale of $24,000, the stamps affixed were $24.00, indicating a federal conveyance tax rate of .1% on these transactions at the time [click here].

10. HDC/11/27/1871/04

11. HDC/05/02/1872/02; NHDP/06/05/1871/04; NHDP/06/06/1871/04; NHJC/06/29/1872/02. Woodruff [p101] is incorrect when she says Tyler City was never anything more than a flag stop.

12. HDC/03/24/1873/04

13. HDC/08/29/1873/04

14. NHJC/11/02/1871/02; NHDP/10/07/1871/02; NHDP/11/06/1871/02

15. NHER/05/29/1874/02

16. NHER/07/03/1888/01; NHER/07/13/1888/01; NHER/07/31/1888/01

17. NHER/07/17/1890/01; HC/07/19/1890/05; NHER/07/22/1890/04;

NHER/07/28/1890/01; NHER/07/30/1890/01; NHER/08/01/1890/03;

NHER/07/17,22,28,30/1890. See also The African Abroad, William Henry Ferris, p. 861.

18. NHER/08/01/1890/03

19. NHER/08/07/1890/01

20. NHER/08/07/1890/01; HC/06/03/1921/18; NYT/06/21/1921/12

21. NHER/08/01/1890/02; NHER/08/04/1890/02

22. NHER/01/17/1884/01

23. HDC/05/19/1884/04

24. NHER/03/12/1886/01

25. NHER/12/22/1885/01

26. NHER/04/17/1886/04; NHER/06/05/1886/02; NHER/01/13/1887/??

27. HDC/01/22/1877/04

28. NHER/06/23/1887/03

29. NHER/11/27/1888/01

30. NHER/10/27/1893/03

31. NHER/02/23/1889/02

32. NHER/02/26/1889/02

33. NHER/05/29/1890/04

34. NHER/03/09/1892/04; NHER/04/05/1893/04

35. NHER/10/28/98/02; HC/10/29/1898/13

36. NHER/11/26/1898/01

37. NHJC/06/04/1877/04

38. NHER/03/14/1898/02

39. NHER/03/29/1882/01

40. HC/04/24/1901/02

41. Callahan, HDC/07/31/1883/04; Berry, NHER/07/15/1884/01; tallow, NHER/07/11/1885/04; Quinn, NHER/06/02/1886/01; construction train, NHER/12/24/1889/01; baseball, HC/05/07/1892/06; Vetterman, NHER/10/11/1895/02; Pepe, NHER/07/15/1897/04; Beck, NYT/11/04/1897/05; inspection car, NHER/11/05/1898/02;

horse, HC/09/21/1903/13; Army, HC/08/12/1912/02; Edwards, HC/06/17/1917/17.

42. Warmsley, Arthur J. Connecticut Post Offices and Postmarks. Hartford, Connecticut: Connecticut Printers, 1977. p238. Warmsley gives the dates of 1874 to 1916.

43. Bowman, NHER/05/10/1893/01; Merwin, NYT/11/14/1894/08; Von Benschotein, NHER/07/29/1895/01, NYT/08/18/1910/09, HC/08/29/1910/10]; Wells, HC/01/05/1911/01; vacant, HC/10/26/1915/19; final, HC/06/19/1916/11. See also the United States Official Postal Guide, which shows Tyler City appearing for the last time in 1916 [click here], and is gone by 1920 [click here].

44. NHER/12/31/1904/??; HC/12/29/1904/11; HC/01/10/1905/02; HC/ 04/11/1905/07; HC/04/15/1905/02; HC/12/04/1906/12.

45. The citation for the Supreme Court case is 203 U.S. 372. There are numerous lower court cases and rulings as well.

1. History of Orange, North Milford, Connecticut, 1639-1949, p. 101-103. Mary Woodruff was born on November 3, 1876 and died on February 18, 1973, at the age of 96. While there may be a few minor errors in her book, she is certainly a primary source, and, in fact, our only source for much of what she wrote about during her lifetime. Would that she had left even more detail of what she lived through.

2. NHSR/10/27/1929/03; ES/11/01/1929/13

3. In the ads and other primary sources, both businesses are said to be on State St., though the street numbers vary.

4. NHDP/10/30/1871/02 gives Halliwell's first name incorrectly as William and also says the property had been purchased prior to October 31. NHJC/10/30/1871/02 says Halliwell and Ferry have purchased the Bradley farm. See listings in Greenough, Jones & Co's New Directory... of the City of New Haven (1874): 102, 121 [click here] and other city directories. This directory says that Ferry lives in Tyler City and that Halliwell is in real estate, with a home address of 37 Davenport Ave. A newspaper article says he was a well-known tea wholesaler in 1871, apparently before he began his real estate career [NHJC/11/20/1871/02].

5. HDC/11/21/1871/04

6. As quoted in Roby Raymond, "Tyler City Tycoons," Connecticut Magazine, July, 1972

7. NHER/11/16/1871/02

8. NHER/03/09/1872/??; NHDP/07/02/1872/01

9. Woodruff says that the auction was July 10. Perhaps the source she was using gave a tally of sales at the end of week starting on July 2. The Register article says there were "several gala days" in the flurry of buying. NHER/07/03/1872/02 and NHJC/07/03//1872/02 both give the same list of names and numbers of lots purchased: James Cusick, four; James Lord, five; J.H. Winfield, one; Charles S. Pratt, one; T.N. Tuttle, two; Nathan Dalzell, two; J.L. Moore, one; Thomas Bright, one; James Taylor, two; Florence Welhauser, two; Christian Meyer, two; Mrs. Beecher, four; Charles Reiul, two; Professor Turner, two; A.H. Cornwall, two; Barbara Saunders, seven; William Lindley, three; James L. Townsend, four; Horace Hubbell, four; W.G. Hooker, two; T.H. Fagan, two; N. Cohen, one; Charles Hildebrand, two; E.B. Stevens, two; Martin Tuttle, one; John F. Comstock, one; George Beckwith [the surveyor], three; William Witchler, one; Nicholas O'Hara, one; G.A. Huntoon, one; L. Schulke, one; W.H. Hazel, one; Charles Horsman, two; James Taylor, two; C.E. Burwell, two; W.H. Kenyon, two; William McWeeney, two; Joseph Colton, one; S. Cohen, one; B.F. Thomas, New York, six. We have the sale deed delivering lots 496 and 498 for "one dollar and other valuable considerations" to E. Charles Hildebrand. The 50-cent amount of the U. S. Internal Revenue stamps to be affixed indicate a sales price of $500 for the two lots, giving a price of $250 each. On the Bradley farm sale of $24,000, the stamps affixed were $24.00, indicating a federal conveyance tax rate of .1% on these transactions at the time [click here].

10. HDC/11/27/1871/04

11. HDC/05/02/1872/02; NHDP/06/05/1871/04; NHDP/06/06/1871/04; NHJC/06/29/1872/02. Woodruff [p101] is incorrect when she says Tyler City was never anything more than a flag stop.

12. HDC/03/24/1873/04

13. HDC/08/29/1873/04

14. NHJC/11/02/1871/02; NHDP/10/07/1871/02; NHDP/11/06/1871/02

15. NHER/05/29/1874/02

16. NHER/07/03/1888/01; NHER/07/13/1888/01; NHER/07/31/1888/01

17. NHER/07/17/1890/01; HC/07/19/1890/05; NHER/07/22/1890/04;

NHER/07/28/1890/01; NHER/07/30/1890/01; NHER/08/01/1890/03;

NHER/07/17,22,28,30/1890. See also The African Abroad, William Henry Ferris, p. 861.

18. NHER/08/01/1890/03

19. NHER/08/07/1890/01

20. NHER/08/07/1890/01; HC/06/03/1921/18; NYT/06/21/1921/12

21. NHER/08/01/1890/02; NHER/08/04/1890/02

22. NHER/01/17/1884/01

23. HDC/05/19/1884/04

24. NHER/03/12/1886/01

25. NHER/12/22/1885/01

26. NHER/04/17/1886/04; NHER/06/05/1886/02; NHER/01/13/1887/??

27. HDC/01/22/1877/04

28. NHER/06/23/1887/03

29. NHER/11/27/1888/01

30. NHER/10/27/1893/03

31. NHER/02/23/1889/02

32. NHER/02/26/1889/02

33. NHER/05/29/1890/04

34. NHER/03/09/1892/04; NHER/04/05/1893/04

35. NHER/10/28/98/02; HC/10/29/1898/13

36. NHER/11/26/1898/01

37. NHJC/06/04/1877/04

38. NHER/03/14/1898/02

39. NHER/03/29/1882/01

40. HC/04/24/1901/02

41. Callahan, HDC/07/31/1883/04; Berry, NHER/07/15/1884/01; tallow, NHER/07/11/1885/04; Quinn, NHER/06/02/1886/01; construction train, NHER/12/24/1889/01; baseball, HC/05/07/1892/06; Vetterman, NHER/10/11/1895/02; Pepe, NHER/07/15/1897/04; Beck, NYT/11/04/1897/05; inspection car, NHER/11/05/1898/02;

horse, HC/09/21/1903/13; Army, HC/08/12/1912/02; Edwards, HC/06/17/1917/17.

42. Warmsley, Arthur J. Connecticut Post Offices and Postmarks. Hartford, Connecticut: Connecticut Printers, 1977. p238. Warmsley gives the dates of 1874 to 1916.

43. Bowman, NHER/05/10/1893/01; Merwin, NYT/11/14/1894/08; Von Benschotein, NHER/07/29/1895/01, NYT/08/18/1910/09, HC/08/29/1910/10]; Wells, HC/01/05/1911/01; vacant, HC/10/26/1915/19; final, HC/06/19/1916/11. See also the United States Official Postal Guide, which shows Tyler City appearing for the last time in 1916 [click here], and is gone by 1920 [click here].

44. NHER/12/31/1904/??; HC/12/29/1904/11; HC/01/10/1905/02; HC/ 04/11/1905/07; HC/04/15/1905/02; HC/12/04/1906/12.

45. The citation for the Supreme Court case is 203 U.S. 372. There are numerous lower court cases and rulings as well.