Track 8 - Railroads and Orphans: The Six Lives of South Campus Hall

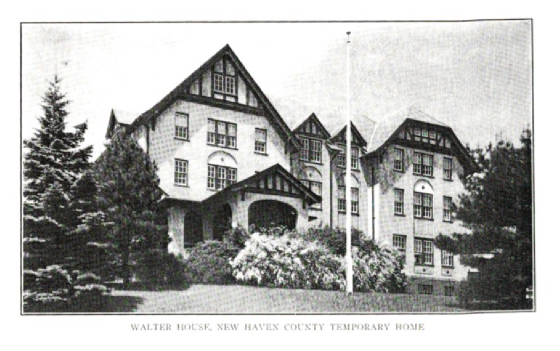

The Walter House, pictured ca. 1935, after being purchased and added to the New Haven County Temporary Home for Dependent and Neglected Children.

__________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

[8.0] While not directly connected to the railroad material that is the focus of this site, the history of the New Haven County Temporary Home for Dependent and Neglected Children is not unrelated. After legislation was passed in 1883 creating these homes in each of Connecticut's eight counties, the first location in New Haven County was in the short-lived, railroad boom town of Tyler City, as has been shown on Track 1. The home’s origin there was due, at least in part, to the fact that Tyler City did not flourish as hoped and anticipated, and other uses were found for some of the vacant structures built there. While additional scrutiny of the sources would be necessary to clarify the point, the location was undoubtedly aided by the fact that it was accessible by rail. The idyllic rural location was likely also a draw. According to historian Mary Woodruff, the railroad, or lack of better access to it, was the reason the home left Tyler City when the town refused to build sidewalks to the railroad station. That distance being minimal, one wonders how much a role this factor played in the home's subsequent move to New Haven. The home found a third and final location in what is today West Haven, property that New Haven College, now the University of New Haven, [click here] purchased in 1960. This is right up Campbell Ave. from where the old NH&D crossed through what is now the VA Hospital property. Undoubtedly the ‘inmate’ children, their relatives, and government officials used the railroad to come, to go, and to visit the home at all the locations but especially at its original and final ones.

Our story involves the mysterious ‘third building’ that came along with NHC’s purchase. The main orphanage structure, UNH’s Maxcy Hall [click here], and the building still called the Gate House today were built together in matching brick Colonial style in 1909. The third building, located across Ruden Street and then called the Walter House, is now UNH’s South Campus Hall. With its stucco exterior, Tudor-style gables, and residential ambience, it seems to have been a thing apart from the other two buildings. What of its origins and history? Whence the name Walter? A previous owner? A benefactor? A mystery? Using documents from several local repositories as well as the Internet, a fascinating history emerges for this building. This saga entails unwed mothers, fraternal brothers, county wards, nuns in need, bespectacled librarians, and college administrators. One story, with six distinct chapters, in what amounts to nearly a century of social service in this building, intertwining events of local, regional, and national significance.

[8.1] Chapter One opens in 1915. The building was constructed as the third location of the New Haven branch of the National Florence Crittenton Mission. The mission was founded by Charles N. Crittenton in New York City in 1883 in memory of his daughter Florence, who had died at age four of scarlet fever. Its aim was to rescue young women in trouble and the need was great. Drugs, prostitution, and white slavery were serious social problems in urban areas and out-of-wedlock pregnancy was stigmatized. By 1897 there were 47 missions across the country with many more to come, in some foreign countries as well. In 1898, President McKinley signed a special act of Congress giving the mission a national charter, the first such organization to be so honored, leading to its continued existence today. The local branch was established in 1900 and ran a house in New Haven at 78 Ward St. until need for a larger facility necessitated a move to 432 Oak St. Overcrowding and deteriorating neighborhood conditions there soon led to a call for yet more space and a better location. Buoyed by the generosity of local churches and contributors, the mission found “an adequate piece of land in a quiet, beautiful suburb of New Haven.” This was here in Allingtown, a section of what was then Orange; West Haven has only been a town since 1921. The land was obtained from local farmer Seaman B. Smith and his wife Charlotte A. Smith on June 10, 1912 for $2,500. Their home was across Campbell Avenue opposite UNH’s Kaplan Hall.

A gracious residential-style facility was built on the purchased land, to be just that, a residence, not an institution like the county home across the road. The building was designed by respected New Haven architect C.F. Townsend. It cost about $50,000, intended to house 50 girls and handful of staff. It opened to the girls in December of 1915. It was a beautiful, modern, fireproof facility, with electric lights and steam heat. One girl described it as a “large gray castle” and another wrote “We live in a glass mansion away up on a hill, and have a wonderful view.” There was a sizeable kitchen, and dining and assembly rooms on the main floor and a large laundry in the basement. On the upper levels there were matrons’ facilities, some private rooms reserved usually for the “honors girls” and mothers with babies, and dormitories. There was also a nursery - daycare for the babies, typically about a dozen in the home at a time - while the mothers worked. The mission encouraged the young mothers to keep their babies rather than put them up for adoption, which was considered a last resort. This recognition of mother and child as a core family was revolutionary for the time.

A daily schedule of activities began at 6:30 in the morning, and included prayer devotions, a full day of work with meals and recreation interspersed, a grammar-school class period, study hour, and lights out by 8:30. Work assignments rotated so that the girls learned every aspect of household management. Sewing, laundry, and gardening - the vegetable garden was out back on the south side of the house - sustained the residents and provided support for the mission from income earned through work done by the girls. Athletics were added to the regimen in 1922-1923 when $10,000 was spent to construct a gymnasium, which is the rear, or west, wing that extends from the main house toward Cook Ave. A large stone fireplace in the gymnasium added cheer and warmth. A Protestant religious tone governed the mission which looked to care for the moral, spiritual, and physical welfare of its charges as it prepared the girls for reentry into the world as productive citizens. By 1928, nearly 500 girls, of all nationalities and faiths and from towns all over Connecticut, had been helped by the mission.

Finances, of course, were always a concern, even with state money and charitable donations. Constructing the mission at just half the size of the original plans, a $12,000 mortgage was still needed. It was paid off by 1921 and, while the annual reports seem to show a stable balance sheet, it is clear that all the money taken in each year was used for operating expenses. A Florence Crittenton gift shop opened in New Haven in 1927, probably for extra income, and perhaps helped a little. However, somewhat suddenly, in late 1928 or early 1929, the mission decided to abandon its idyllic location for financial reasons and put the building up for sale. It worried about finding a buyer for such an expensive piece of real estate and wound up settling for $50,000, about half the estimated value at the time. It moved, sadly and ironically, back to smaller quarters in the Elm City at 43 Division St. It was likely the victim of its own bold vision and zeal in building a mission designed to its specifications, a more expensive proposition than purchasing an existing building for less money, as was the case with other Crittenton missions. The reasons for the mission’s retreat may well bear further examination. In any case, it last appears in the listings in the New Haven city directories in 1931.

[8.2] Chapter Two of our saga opens on July 19, 1929. The new owner of the mission with its three-plus acres of land was the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. The New Haven Evening Register article was jocularly subtitled “Antlered Herd Acquires New Home.” With their religious values and social-service aims, the new owners were somewhat akin to the old. Founded in 1927, West Haven Lodge 1537 had grown to 400 members by 1929. It met first at the Thompson School on Richards St., and then at 265 Main St., and was planning to build its own facility when the Crittenton property became available. The mission was described as “one of the most ideal clubhouses” with its own picnic grounds adjoining the park and hall owned by the Harugari Liedertafel, a German singing society still in existence in 2012 [click here]. The Elks kept the building until late 1935 when, perhaps for financial reasons - by then the Great Depression was on - it was again sold. The “antlered herd” retreated to their original Main St. location where they still are. The West Haven Town Crier reported shortly after the move that the Elks missed the ballroom, probably in the gymnasium wing, that they had on Campbell Avenue. Ironically, after vacating the fireproof Crittenton building, there was a fire at the Main St. lodge in 1949, which displaced the members temporarily and destroyed their records. Unfortunately, as a result, no photos survive of the Crittenton property as an Elks lodge, and no members go far enough back to recall it either. Lodge 1537 is, nevertheless, still going strong today [click here].

[8.3] Chapter Three commences with the purchase of the home by New Haven County on December 19, 1935, as an annex to the adjacent orphanage. Many uses were suggested for the newly acquired building, including a hospital facility and a training school for either the boys or the girls. Ultimately, the latter won out and the importance of separating the sexes won out as well because females were shortly taken completely out of the wing they occupied in the main orphanage building. The Elks lodge became the residence and training school in domestic science for the older girls, while the youngest girls went to the Gate House. Within a year after the lodge was acquired by the county, it was named the Walter House in honor of Jacob D. Walter, the senior county commissioner. While no documentation has been found to verify this, it has been recently confirmed by a personal friend of Jacob D. Walter. Walter was a powerful and well-known political figure, serving for many years as commissioner, and also as a Cheshire selectman, a state representative, and a U.S. marshal for Connecticut, dutifully enforcing Prohibition ordinances. A visitor studying conditions at the orphanage in 1944 described the Walter House as “an attractive building of the college sorority type,” large enough to care for 25 girls and currently caring for 19. He laments some conditions at the facility, including the lack of recreational amenities. The gymnasium is described as being well-heated but bereft of any equipment, save “a very badly damaged and mutilated cabinet radio-phonograph combination” which was reportedly broken a few months after purchase two years earlier. These and other more serious complaints would lead to the closing of the New Haven county facility and its counterparts in each of the other Connecticut counties ten years later.

[8.4] Chapter Four of this saga begins when the Walter House perhaps rose to its highest level of service. After the county home operation closed in 1955, with the entire property vacant and awaiting sale, the house became the refuge of Dominican nuns from North Guilford whose cloister, the Monastery of Our Lady of Grace [click here], had burned on December 23, 1955. Three nuns died in the fire. The rest rode by bus to first sojourn at Albertus Magnus College, which is staffed by Dominican teaching sisters. The great outpouring of grief and support moved New Haven Mayor Richard C. Lee and Welfare Commissioner Francis Looney to persuade the county to allow the nuns rent-free use of the Walter House until their monastery could be rebuilt. They arrived on January 1, 1956 and temporary renovations were made to accommodate them. Generous donations of food, clothing, and supplies also arrived. New bedding replaced the old, as mattresses were tossed out the windows from the upper floors. The gymnasium was divided into three rooms: a refectory or dining room, a print shop where the nuns continued their work of publishing prayer materials, and a parlor to receive guests, closed off by screens to preserve the cloistered nature of their life. Rooms in the main house were divided with curtains and cotton sheets to create small cells for each of the 39 nuns. The old Crittenton dining room on the Ruden St. side of the main floor was transformed into a chapel. Their chaplain Fr. Reginald Craven, O.P. stayed across Cook Ave. in a house owned by the Brothers of the Holy Cross who staff Notre Dame High School. The chaplain said Mass daily in the chapel - he and the public entered via a separate entrance to the non-cloistered part of the chapel - and ministered to the nuns throughout the time they were here. The sisters were soon living their monastic life again, praying on schedule, and earning money by producing liturgical materials, vestments, rosaries, and altar equipment, now all largely aimed at resurrecting their monastery. On Easter Monday, April 7, 1958, after spending nearly two and a half years at the Walter House, the nuns returned to their rebuilt monastery in North Guilford. Several of the sisters who lived through the tragedy are alive today and, in speaking to them, their gratitude is still obvious for the generosity of the county and all who helped in their time of need. They also still chuckle at the fact that the facility that welcomed them had once been a home for unwed mothers.

[8.5] Chapter Five of the saga of South Campus Hall opens when the entire county property was purchased by New Haven College in June of 1960. Coincidentally and ironically, county government in Connecticut was abolished on October 1, 1960, with county properties reverting to the state. Selling the site to the college was one of the county’s last official acts. Speculation had been rife about the future of the orphanage property, even while the Dominican nuns were in residence, including use as a junior high school, a convalescent home, a jail, and a relocated West Haven town hall, until NHC President Marvin K. Peterson succeeded with the college purchase. Not too long afterward, on May 1, 1962, The New Haven College News reported that the Walters (sic) House was to become the new library, with materials moved from a wing of Maxcy Hall where the library had first been set up, that space being turned into classrooms. The library’s collection numbered some 50,000 book and periodical volumes in those days. Pictures in the UNH Archives show students using the library which occupied the basement, first, and second levels. Some materials in the present Peterson Library still have an ownership stamp showing the library with an address of 1092 Campbell Avenue. That was the newly minted address from 1915 which the Crittenton mission was given as the first structure ever built on the property and which it passed on to the Elks, the Walter House, and finally the old library. Nothing much appears to have changed on the exterior as the Walter House became the New Haven College Library. The entrance via the covered carriage porch, the porte-cochere, facing Campbell Avenue, had probably been closed earlier and the winding gravel driveway to the porch abandoned. Access and signage was to the rear of the building now, linking it more closely with the main campus.

[8.6] Chapter Six concludes our saga. After UNH’s Peterson Library opened in 1974, the Walter House was completely refurbished and converted from the library to use by admissions, student services, and registrars’ offices, and academic departments as well, largely as it is now. The parking lot in the rear was paved and expanded out to the street, covering the site of the Crittenton-era flower garden and playground for the girls. The old metal fire escape in the back was taken down, as well as the fire door on the Ruden St. side of the front which had been used as the public’s chapel entrance. The two-story bay window in the middle of the building on the Ruden St. side was shorn off and replaced by an enclosed, emergency-exit staircase. The enclosure’s slightly different shade of color is still apparent today. In 1975, UNH purchased Harugari Hall from Notre Dame H.S. [click here]. The high school had begun in the hall, which the Brothers of the Holy Cross purchased in 1946 from the Harugari society, before building the new high school on the hill behind the hall. Now, with two UNH buildings across Ruden Street in a semblance of a “southern” campus, the Walter House was renamed South Campus Hall, as it still is currently known.

Today, the UNH registrars’ offices are in what was the 1922 gymnasium, while faculty, departmental, and administrative offices occupy the 1915 main building. With the number of transformations the building has undergone, it is certain that each office in the present configuration has seen a variety of uses over the years. Nursery, dining room, gymnasium, dormitory, parlor, ballroom, nuns’ cloister, chapel, print shop, library stacks. Even if these walls could speak, they have been rechristened so many times they might well not remember! Perhaps there are not enough generations for a James Michener novel here, but South Campus Hall, UNH’s original 'third building' has had a remarkable existence. Six chapters in nearly a century of social service. A long history that attained national significance in the Crittenton era and that enriches West Haven today with the unique events that have taken place within its walls. It is of interest to us that the New Haven & Derby RR played a role in this institution, however peripheral that role might have been.

Our story involves the mysterious ‘third building’ that came along with NHC’s purchase. The main orphanage structure, UNH’s Maxcy Hall [click here], and the building still called the Gate House today were built together in matching brick Colonial style in 1909. The third building, located across Ruden Street and then called the Walter House, is now UNH’s South Campus Hall. With its stucco exterior, Tudor-style gables, and residential ambience, it seems to have been a thing apart from the other two buildings. What of its origins and history? Whence the name Walter? A previous owner? A benefactor? A mystery? Using documents from several local repositories as well as the Internet, a fascinating history emerges for this building. This saga entails unwed mothers, fraternal brothers, county wards, nuns in need, bespectacled librarians, and college administrators. One story, with six distinct chapters, in what amounts to nearly a century of social service in this building, intertwining events of local, regional, and national significance.

[8.1] Chapter One opens in 1915. The building was constructed as the third location of the New Haven branch of the National Florence Crittenton Mission. The mission was founded by Charles N. Crittenton in New York City in 1883 in memory of his daughter Florence, who had died at age four of scarlet fever. Its aim was to rescue young women in trouble and the need was great. Drugs, prostitution, and white slavery were serious social problems in urban areas and out-of-wedlock pregnancy was stigmatized. By 1897 there were 47 missions across the country with many more to come, in some foreign countries as well. In 1898, President McKinley signed a special act of Congress giving the mission a national charter, the first such organization to be so honored, leading to its continued existence today. The local branch was established in 1900 and ran a house in New Haven at 78 Ward St. until need for a larger facility necessitated a move to 432 Oak St. Overcrowding and deteriorating neighborhood conditions there soon led to a call for yet more space and a better location. Buoyed by the generosity of local churches and contributors, the mission found “an adequate piece of land in a quiet, beautiful suburb of New Haven.” This was here in Allingtown, a section of what was then Orange; West Haven has only been a town since 1921. The land was obtained from local farmer Seaman B. Smith and his wife Charlotte A. Smith on June 10, 1912 for $2,500. Their home was across Campbell Avenue opposite UNH’s Kaplan Hall.

A gracious residential-style facility was built on the purchased land, to be just that, a residence, not an institution like the county home across the road. The building was designed by respected New Haven architect C.F. Townsend. It cost about $50,000, intended to house 50 girls and handful of staff. It opened to the girls in December of 1915. It was a beautiful, modern, fireproof facility, with electric lights and steam heat. One girl described it as a “large gray castle” and another wrote “We live in a glass mansion away up on a hill, and have a wonderful view.” There was a sizeable kitchen, and dining and assembly rooms on the main floor and a large laundry in the basement. On the upper levels there were matrons’ facilities, some private rooms reserved usually for the “honors girls” and mothers with babies, and dormitories. There was also a nursery - daycare for the babies, typically about a dozen in the home at a time - while the mothers worked. The mission encouraged the young mothers to keep their babies rather than put them up for adoption, which was considered a last resort. This recognition of mother and child as a core family was revolutionary for the time.

A daily schedule of activities began at 6:30 in the morning, and included prayer devotions, a full day of work with meals and recreation interspersed, a grammar-school class period, study hour, and lights out by 8:30. Work assignments rotated so that the girls learned every aspect of household management. Sewing, laundry, and gardening - the vegetable garden was out back on the south side of the house - sustained the residents and provided support for the mission from income earned through work done by the girls. Athletics were added to the regimen in 1922-1923 when $10,000 was spent to construct a gymnasium, which is the rear, or west, wing that extends from the main house toward Cook Ave. A large stone fireplace in the gymnasium added cheer and warmth. A Protestant religious tone governed the mission which looked to care for the moral, spiritual, and physical welfare of its charges as it prepared the girls for reentry into the world as productive citizens. By 1928, nearly 500 girls, of all nationalities and faiths and from towns all over Connecticut, had been helped by the mission.

Finances, of course, were always a concern, even with state money and charitable donations. Constructing the mission at just half the size of the original plans, a $12,000 mortgage was still needed. It was paid off by 1921 and, while the annual reports seem to show a stable balance sheet, it is clear that all the money taken in each year was used for operating expenses. A Florence Crittenton gift shop opened in New Haven in 1927, probably for extra income, and perhaps helped a little. However, somewhat suddenly, in late 1928 or early 1929, the mission decided to abandon its idyllic location for financial reasons and put the building up for sale. It worried about finding a buyer for such an expensive piece of real estate and wound up settling for $50,000, about half the estimated value at the time. It moved, sadly and ironically, back to smaller quarters in the Elm City at 43 Division St. It was likely the victim of its own bold vision and zeal in building a mission designed to its specifications, a more expensive proposition than purchasing an existing building for less money, as was the case with other Crittenton missions. The reasons for the mission’s retreat may well bear further examination. In any case, it last appears in the listings in the New Haven city directories in 1931.

[8.2] Chapter Two of our saga opens on July 19, 1929. The new owner of the mission with its three-plus acres of land was the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. The New Haven Evening Register article was jocularly subtitled “Antlered Herd Acquires New Home.” With their religious values and social-service aims, the new owners were somewhat akin to the old. Founded in 1927, West Haven Lodge 1537 had grown to 400 members by 1929. It met first at the Thompson School on Richards St., and then at 265 Main St., and was planning to build its own facility when the Crittenton property became available. The mission was described as “one of the most ideal clubhouses” with its own picnic grounds adjoining the park and hall owned by the Harugari Liedertafel, a German singing society still in existence in 2012 [click here]. The Elks kept the building until late 1935 when, perhaps for financial reasons - by then the Great Depression was on - it was again sold. The “antlered herd” retreated to their original Main St. location where they still are. The West Haven Town Crier reported shortly after the move that the Elks missed the ballroom, probably in the gymnasium wing, that they had on Campbell Avenue. Ironically, after vacating the fireproof Crittenton building, there was a fire at the Main St. lodge in 1949, which displaced the members temporarily and destroyed their records. Unfortunately, as a result, no photos survive of the Crittenton property as an Elks lodge, and no members go far enough back to recall it either. Lodge 1537 is, nevertheless, still going strong today [click here].

[8.3] Chapter Three commences with the purchase of the home by New Haven County on December 19, 1935, as an annex to the adjacent orphanage. Many uses were suggested for the newly acquired building, including a hospital facility and a training school for either the boys or the girls. Ultimately, the latter won out and the importance of separating the sexes won out as well because females were shortly taken completely out of the wing they occupied in the main orphanage building. The Elks lodge became the residence and training school in domestic science for the older girls, while the youngest girls went to the Gate House. Within a year after the lodge was acquired by the county, it was named the Walter House in honor of Jacob D. Walter, the senior county commissioner. While no documentation has been found to verify this, it has been recently confirmed by a personal friend of Jacob D. Walter. Walter was a powerful and well-known political figure, serving for many years as commissioner, and also as a Cheshire selectman, a state representative, and a U.S. marshal for Connecticut, dutifully enforcing Prohibition ordinances. A visitor studying conditions at the orphanage in 1944 described the Walter House as “an attractive building of the college sorority type,” large enough to care for 25 girls and currently caring for 19. He laments some conditions at the facility, including the lack of recreational amenities. The gymnasium is described as being well-heated but bereft of any equipment, save “a very badly damaged and mutilated cabinet radio-phonograph combination” which was reportedly broken a few months after purchase two years earlier. These and other more serious complaints would lead to the closing of the New Haven county facility and its counterparts in each of the other Connecticut counties ten years later.

[8.4] Chapter Four of this saga begins when the Walter House perhaps rose to its highest level of service. After the county home operation closed in 1955, with the entire property vacant and awaiting sale, the house became the refuge of Dominican nuns from North Guilford whose cloister, the Monastery of Our Lady of Grace [click here], had burned on December 23, 1955. Three nuns died in the fire. The rest rode by bus to first sojourn at Albertus Magnus College, which is staffed by Dominican teaching sisters. The great outpouring of grief and support moved New Haven Mayor Richard C. Lee and Welfare Commissioner Francis Looney to persuade the county to allow the nuns rent-free use of the Walter House until their monastery could be rebuilt. They arrived on January 1, 1956 and temporary renovations were made to accommodate them. Generous donations of food, clothing, and supplies also arrived. New bedding replaced the old, as mattresses were tossed out the windows from the upper floors. The gymnasium was divided into three rooms: a refectory or dining room, a print shop where the nuns continued their work of publishing prayer materials, and a parlor to receive guests, closed off by screens to preserve the cloistered nature of their life. Rooms in the main house were divided with curtains and cotton sheets to create small cells for each of the 39 nuns. The old Crittenton dining room on the Ruden St. side of the main floor was transformed into a chapel. Their chaplain Fr. Reginald Craven, O.P. stayed across Cook Ave. in a house owned by the Brothers of the Holy Cross who staff Notre Dame High School. The chaplain said Mass daily in the chapel - he and the public entered via a separate entrance to the non-cloistered part of the chapel - and ministered to the nuns throughout the time they were here. The sisters were soon living their monastic life again, praying on schedule, and earning money by producing liturgical materials, vestments, rosaries, and altar equipment, now all largely aimed at resurrecting their monastery. On Easter Monday, April 7, 1958, after spending nearly two and a half years at the Walter House, the nuns returned to their rebuilt monastery in North Guilford. Several of the sisters who lived through the tragedy are alive today and, in speaking to them, their gratitude is still obvious for the generosity of the county and all who helped in their time of need. They also still chuckle at the fact that the facility that welcomed them had once been a home for unwed mothers.

[8.5] Chapter Five of the saga of South Campus Hall opens when the entire county property was purchased by New Haven College in June of 1960. Coincidentally and ironically, county government in Connecticut was abolished on October 1, 1960, with county properties reverting to the state. Selling the site to the college was one of the county’s last official acts. Speculation had been rife about the future of the orphanage property, even while the Dominican nuns were in residence, including use as a junior high school, a convalescent home, a jail, and a relocated West Haven town hall, until NHC President Marvin K. Peterson succeeded with the college purchase. Not too long afterward, on May 1, 1962, The New Haven College News reported that the Walters (sic) House was to become the new library, with materials moved from a wing of Maxcy Hall where the library had first been set up, that space being turned into classrooms. The library’s collection numbered some 50,000 book and periodical volumes in those days. Pictures in the UNH Archives show students using the library which occupied the basement, first, and second levels. Some materials in the present Peterson Library still have an ownership stamp showing the library with an address of 1092 Campbell Avenue. That was the newly minted address from 1915 which the Crittenton mission was given as the first structure ever built on the property and which it passed on to the Elks, the Walter House, and finally the old library. Nothing much appears to have changed on the exterior as the Walter House became the New Haven College Library. The entrance via the covered carriage porch, the porte-cochere, facing Campbell Avenue, had probably been closed earlier and the winding gravel driveway to the porch abandoned. Access and signage was to the rear of the building now, linking it more closely with the main campus.

[8.6] Chapter Six concludes our saga. After UNH’s Peterson Library opened in 1974, the Walter House was completely refurbished and converted from the library to use by admissions, student services, and registrars’ offices, and academic departments as well, largely as it is now. The parking lot in the rear was paved and expanded out to the street, covering the site of the Crittenton-era flower garden and playground for the girls. The old metal fire escape in the back was taken down, as well as the fire door on the Ruden St. side of the front which had been used as the public’s chapel entrance. The two-story bay window in the middle of the building on the Ruden St. side was shorn off and replaced by an enclosed, emergency-exit staircase. The enclosure’s slightly different shade of color is still apparent today. In 1975, UNH purchased Harugari Hall from Notre Dame H.S. [click here]. The high school had begun in the hall, which the Brothers of the Holy Cross purchased in 1946 from the Harugari society, before building the new high school on the hill behind the hall. Now, with two UNH buildings across Ruden Street in a semblance of a “southern” campus, the Walter House was renamed South Campus Hall, as it still is currently known.

Today, the UNH registrars’ offices are in what was the 1922 gymnasium, while faculty, departmental, and administrative offices occupy the 1915 main building. With the number of transformations the building has undergone, it is certain that each office in the present configuration has seen a variety of uses over the years. Nursery, dining room, gymnasium, dormitory, parlor, ballroom, nuns’ cloister, chapel, print shop, library stacks. Even if these walls could speak, they have been rechristened so many times they might well not remember! Perhaps there are not enough generations for a James Michener novel here, but South Campus Hall, UNH’s original 'third building' has had a remarkable existence. Six chapters in nearly a century of social service. A long history that attained national significance in the Crittenton era and that enriches West Haven today with the unique events that have taken place within its walls. It is of interest to us that the New Haven & Derby RR played a role in this institution, however peripheral that role might have been.