Track 6 - The Iron Horse in New Haven: The Evolution of a Railroad Capital, 1838-1920

The story of New Haven’s development as a rail transportation hub is the stuff of documentary history. It is a multi-chaptered epic, sometimes laced with drama, perhaps unlike any in this country for a city of comparable size. Six separate railroads built into the Elm City from 1838 to 1871, paralleling and eclipsing the six turnpikes that radiated similarly out of New Haven. ‘Railroad fever’ succeeded ‘canal mania’ even as river and Long Island Sound transport continued to compete with, yet complement, the railroads, each of which brought new track, engine houses, turntables, freight houses, yards, wharves, office buildings, or other facilities. Passenger stations were generally shared by more than one road but even this was with some intriguing exceptions. The New York, New Haven and Hartford RR emerged dominant over this assemblage and developed it to its greatest extent around 1920. This paper hopes to broadly detail the origins of the separate facilities in New Haven and their evolution into the amalgam that the New Haven operated at its height. Much of this research relies on the invaluable accounts found in New Haven and other city newspapers. Primary source documents, important secondary works, and historical maps were also consulted. The Bailey and Hazen birds-eye map of 1879 [click here] is the most helpful graphic item, showing the facilities of the six original railroads in verifiable detail.1 Clarifications and comments on this work are welcome in what, like all good history, is intended to contribute to an evolving understanding of the past. The scholarly exchange of information contained here is encouraged. Reproduction in its entirety or in substantial part is prohibited under personal copyright privileges retained by the author.

Track 6.1: The Three Pioneer Railroads, 1838 - 1848

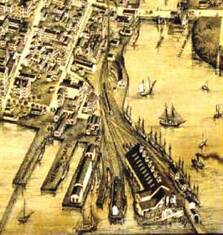

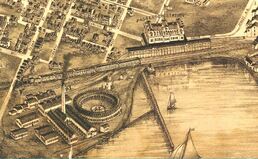

[6.1.1] The Hartford and New Haven RR was the city’s first steam railroad. It was completed on December 14, 1839, its purpose in part to join what were then the state’s two capitals. While Hartford was left with the sole honor in 1875, this shared political status bred rival commercial interests that would last well into the next century.2 Despite the fact that the H&NH was headquartered in the northern city, most of the funding came from New Haven, which was seeking a share of the Connecticut River traffic that Hartford and Middletown controlled. The H&NH considered routes via New Britain, Middletown, and Meriden, with the latter chosen as the most direct and least expensive. On the southern end, the Hartford road built to Steamboat Wharf, also called Belle Dock in honor of the steamer Belle that sailed from there. It was located at the westerly approach to Tomlinson’s Bridge at the mouth of the Quinnipiac River. The railroad bought a controlling interest in this toll-bridge company to gain the property it needed. A large freight depot, engine house, passenger facility, and dock were erected by the H&NH to connect with boats to New York. For the next decade this was to be the sole terminus of New Haven’s only railroad, bringing ever more traffic to and from Belle Dock after the road’s extension to Springfield in 1844. By 1850, the H&NH would also be operating branch roads from New Britain and Middletown feeding into its mainline at Berlin.

[6.1.1] The Hartford and New Haven RR was the city’s first steam railroad. It was completed on December 14, 1839, its purpose in part to join what were then the state’s two capitals. While Hartford was left with the sole honor in 1875, this shared political status bred rival commercial interests that would last well into the next century.2 Despite the fact that the H&NH was headquartered in the northern city, most of the funding came from New Haven, which was seeking a share of the Connecticut River traffic that Hartford and Middletown controlled. The H&NH considered routes via New Britain, Middletown, and Meriden, with the latter chosen as the most direct and least expensive. On the southern end, the Hartford road built to Steamboat Wharf, also called Belle Dock in honor of the steamer Belle that sailed from there. It was located at the westerly approach to Tomlinson’s Bridge at the mouth of the Quinnipiac River. The railroad bought a controlling interest in this toll-bridge company to gain the property it needed. A large freight depot, engine house, passenger facility, and dock were erected by the H&NH to connect with boats to New York. For the next decade this was to be the sole terminus of New Haven’s only railroad, bringing ever more traffic to and from Belle Dock after the road’s extension to Springfield in 1844. By 1850, the H&NH would also be operating branch roads from New Britain and Middletown feeding into its mainline at Berlin.

[6.1.2] From the Bailey and Hazen 1879 map, the Hartford and New Haven's terminus at Belle Dock is shown here. This would evolve into what was later called the Belle Dock branch of the NYNH&H with most of these facilities in place through much of the next century. The Tomlinson Bridge heads off down to the right of the railroad terminus.

[6.1.3] The New Haven and Northampton RR was the second road to open. This entity emerged from the ingenious conversion of the Farmington Canal, which had reached its namesake town in 1828 and had connected in Massachusetts with the Hampshire and Hampton Canal all the way to Northampton by 1835. Backed by the city and never a great financial success, it nevertheless moved a considerable amount of freight in its later years and boosted the economic life of its terminal cities and towns along it line. The canal towpath was used as most of the railroad right of way. By January 18, 1848 trains were running to Plainville. A New Haven terminus with passenger depot, engine house, and turntable was set up in the block bounded by Hillhouse Ave. and Temple, Grove, and Trumbull Sts.3 Track was laid southward to the harbor basin shortly thereafter in the canal bed that had originally been a stream here called East Creek. The bed was excavated to a greater depth and overhead bridges down to Fair St. were rebuilt for better clearance. The triangle-shaped basin was bounded on the west by Union Wharf, popularly known as Long Wharf for its 4,000-ft. reach out into the harbor. The canal company had enclosed the basin on the south side by building a connecting roadway which would later become an extension of Brewery St. The first train ran to the basin on October 21, 1848 with large crowds cheering along the route.4

[6.1.4] This map is from the 1847-1848 Benham city directory for New Haven. This is the first in the series of directories that would be taken over and published by Price & Lee Co., headquartered right in the Elm City, well into 1960s. Note the Farmington Canal in the center leading down to the triangular basin at the top of the harbor. The canal would become a railroad on the next map. Union Wharf was already better known as Long Wharf for its nearly mile-long reach from the shore.

[6.1.5] The head of Long Wharf in 1868 is shown in this image, with the entire western half of the canal basin filled in. These are the facilities that were jointly built and shared by the NY&NH and its leased Canal road. Notice how the neck of land under the NY&NH track going west is complete now up to Long Wharf. The natural silting of the harbor and the deliberate filling of the flats around the NY&NH trestle over to Spring St. would create the land that would help the Consolidated move much of its infrastructure from here in the 1870s, as well as build its 1875 depot on the 'made land' west of Long Wharf.

Joseph Taylor Collection

Joseph Taylor Collection

[6.1.6] This view from a stereo card looks south and shows the 1848 domed roundhouse used jointly by the NY&NH and the Canal line. We know from newspaper articles that the Canal line was building a new roundhouse in 1869 so this view probably dates to the mid-1860s. The extension of the Canal dock was part of the new facilities the NH&N built in anticipation of the ending of its lease to the NY&NH on July 1, 1869. See [6.4.6] below for the Canal line facilities in 1879. The arrow on the map above [6.1.5] points to the Engine House that corresponds to the domed structure which looks more like a cathedral than an engine facility. These magnificent structures, with a turntable under the dome, gradually became outmoded as locomotive sizes grew. The NY&NH was also building its new facilities to the west at this time.4a

[6.1.7] The New York and New Haven RR was coincidentally expected to present an engine at the basin on the very same evening the NH&N reached it, surely a remarkable sight for the Elm City. New Haven’s third railroad was nearly complete after four years of work both in Connecticut and in the Empire State where it was headquartered and where it finally arranged to share the New York and Harlem RR’s right of way from Williams Bridge to New York City. It ran its first regular train to New York from the Elm City on December 27, 1848.5 On the New Haven end, desiring to build from the business and population center of the city along State St., the NY&NH requested and received several route options from Alexander Twining, the Yale engineering professor who would lay out all of Connecticut’s early railroads. Options were explored for going via New Haven’s northerly streets and suburbs even as far as Derby or Danbury to get to New York City or just following the coast, which meant the costly bridging of the numerous rivers emptying into Long Island Sound. The more direct, coastal route prevailed. Click here for a digitized version of Twining's 1845 map of the "Experimental and Located Lines" for the NY&NH. Thought was given to it starting at Belle Dock and proceeding either along Water St. or just off shore but the offer of a lease late in 1847 from Joseph Sheffield, one of the first incorporators of the NY&NH and also president of the Canal road, was accepted and allowed the New York road to use the canal bed alongside the NH&N.6 Turning west from the canal basin, the road was built on pilings over the flats below Water St., which then actually marked the edge of the harbor. Twining said that this could be done fairly easily in the shallow water to start but would require more maintenance in the future. A 21-year lease of the NH&N effective on July 1, 1848, was signed but, due to delays in completing the NY&NH, the Canal road was not handed over until July 1, 1849. While some stockholders of each road were wary of this alliance, advantages came to both sides. The Canal road got annual rental payments, better facilities in New Haven, connections to the west, and a presumed ally in its northward expansion plans. The New York road got the traffic from the NH&N, perpetual use of the canal bed down to the harbor, and access to the basin property there. The railroads jointly set about beginning to turn the latter into usable real estate. The section reclaimed was the northwest corner where they built a substantial freight depot and engine house in October, 1848. On October 26, the Canal road started running trains from Plainville to Bridgeport using the track of its lessee from New Haven, this even before the New York road was fully open. The NH&N utilized the basin facility for western freight and seaborne cargo and, for its northern customers, it used the Temple St. facility, which appears to have been discontinued by January, 1849, probably timed to the completion of a new union station.7 Profitability jumped immediately upon turning the canal into a railroad with a net of just over $37,000 on receipts of $60,000 for 1848.8 The NY&NH later claimed it was losing money on the NH&N, probably due to the high rental payments it had agreed to pay.

[6.1.8] This 1879 view of Henry Austin's 1848 depot is quite accurate. The large atrium on the front, adjacent to the Chapel St. tower (right), was most likely added after 1875 when the structure was converted to an upscale city market. The detailed architectural plans are at the New Haven Museum.

Track 6.2: The 1848 Chapel St. Union Station

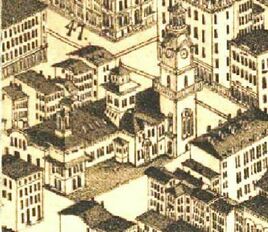

[6.2.1] By late 1847, the NY&NH was contracting for a passenger station. Joseph Sheffield hailed the planned “central depot” and the shared, below-grade, canal-bed route as “... facilities which few other roads and few other Cities enjoy.”9 The station was to take up the entire block between Cherry St. (later Wooster St.) and Chapel St. The depot’s main entrance faced Union St., but access was from all four sides, the rear through a hotel on State St. The station property had previously been the old city market and canal boat landing. The parcel came per the 99-year lease of February 1, 1848 from the city to the Canal road for a nominal 25-cent annual rental on condition that it serve as a public railway station.10 Henry Austin, a popular though not formally trained local architect, had been engaged to plan three depots for the new Canal road at its intended terminal points of New Haven, Plainville, and Collinsville. The NY&NH also retained him. Whereas Austin's other stations were diminutive depots for small towns, the Elm City structure was a colossus. A 300-ft long, architecturally eclectic edifice, it mounted a short pagoda-style dome in the center and asymmetrical towers at each end. The taller one on Chapel St. was a 140-ft Italian-style campanile, a bell tower, the first in the country as part of a rail depot. Also seen as a civic structure, the station rang its bell to sound fire alarms as well as announce trains. While it was suggested that another level be added to the building to house city hall,11 Austin designed that as a separate project completed in 1862 on Church St. Below the depot bell, a four-sided, gas-lit clock, donated by James Brewster, local carriage maker and first president of the H&NH, shone to announce the time in all directions and perhaps to foreshadow the coming of more railroads to this facility. The NY&NH acknowledged the station’s $40,000 cost as its sole extravagance, a deferential gesture to the people of the Elm City. Inside were opulent parlors, “obliging servants,” and later a restaurant.12 Bold exterior form and elegant appointments notwithstanding, function was unfortunately overlooked in the platform area. The subterranean darkness, choked with locomotive heat, fire, and smoke, evoked images and memorable references to the infernal regions from travelers who descended into the canal bed covered by the rear of the station. Steps down on the Union St. side led to the NY&NH track and on the State St. side to the track for the Canal road. The finishing touches on the structure, which was in use by October 28, 1848, came early the next year but did not address the problems that would lead to two remodels in as many years and ever continuing complaints.13

[6.2.2] Thus, by the beginning of 1849, New Haven had three railroads that were functioning more or less as two. Almost immediately the two principal roads found reason for cooperation, albeit guarded. The NY&NH, not interested in freight revenue, was looking to capture as much as it could of the Hartford road’s 300,000 annual passengers to and from New York, the connection with the Western RR in Springfield creating an all-rail route from Boston. The Hartford road, content with the steamboat arrangements it had at Belle Dock, was not particularly interested in a connection with the NY&NH and feared reprisals from the competing Connecticut River boats. Its other concern was that Canal road would extend north and siphon off its Western RR traffic. The NY&NH assuredly had this fear in mind when it leased the Canal road. The NH&N would get as far as Granby, with branches to Tariffville and to Collinsville, all in 1850. The latter was for the coveted traffic of the Collins Mfg. Co. there and with an eye toward going on to Pittsfield, Mass. At that point, however, the NY&NH quietly began to help stall the NH&N. In return, the Hartford road consented to share the NY&NH’s rental payment on the Canal line, to run H&NH passenger trains into the new Austin depot instead of Belle Dock, and, by April, to suspend its own day steamer, the Commodore, to guarantee more passenger traffic on the NY&NH. This effort was supported by Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose interests in these boats were being subordinated to his investments in both the NY&NH and H&NH. By January 27, 1849, the NY&NH had extended its track from Chapel St. northward to a junction with the H&NH at the ‘tin bridge’ over the Mill River. The metal-covered, wooden deck of the bridge here gave this structure its nickname that was found elsewhere on railroad bridges outfitted similarly. On January 29, 1849, the first H&NH connection was made with a train to New York.14 The fact that the several contracts between the NY&NH and the H&NH all expired on July 1, 1869, the same date as the NY&NH lease of the NH&N was up, seems to show that the principal parties were intent as much on keeping each other in check as simultaneously reining in the Canal road.

Track 6.3: The Second Railroad Trio, 1852-1871

[6.3.1] New Haven’s fourth line, the New Haven and New London RR, aimed for the east in 1852. Planned largely as a link in a shoreline route to Boston, it absorbed the New London and Stonington in 1857 in order to connect with the New York, Providence and Boston RR. Similar to the NY&NH’s earlier challenges, its coastal route came with even larger obstacles. The Connecticut and Thames Rivers, initially too formidable to be bridged, had to be crossed by ferry and this gave inland routes the advantage for the next forty years. The NH&NL came into New Haven via what was then the westerly part of East Haven before this section was annexed by the Elm City in 1881. The NH&NL ran up along the east side of the Quinnipiac River and crossed it on a wooden span just above Grand St. Angling northwest through Fair Haven at grade, it continued toward the point known officially as Shore Line Jct., but also as Mill River Jct. or Tin Bridge. From here it built its own track southward to Grand St. The use of the Austin depot and this right of way were covered in a lease by the NY&NH from December 30, 1851 to the already familiar date of July 1, 1869. The New York road initially refused to sell through tickets to Boston via New London, in deference to its allied Hartford road, until the state legislature passed a bill compelling it do so. Even then it took the U.S. Supreme Court to enforce the law. The NH&NL set up an engine house, turntable, and freight facilities at the foot of Myrtle St. just below the junction on what would soon be known as Railroad Ave., rather than River St. This was on the west bank of the Mill River to which the railroad also had freight access by water, as seen on the Bailey map. Early financial difficulties would see this road reorganized as the Shore Line Railway in 1864. By 1870, with the completion of the bridge over the Connecticut River, this property would be of enough interest to be leased to the NY&NH and brought into that road's subsequent merger with the H&HN. The 'Consolidated' road, already having a monopoly on traffic to New York and not in favor with the public, was to be run by a board consisting of members of all three companies. On September 7, 1870, stockholders of the three entities gathered at separate meetings and approved the combined operation.15

Track 6.2: The 1848 Chapel St. Union Station

[6.2.1] By late 1847, the NY&NH was contracting for a passenger station. Joseph Sheffield hailed the planned “central depot” and the shared, below-grade, canal-bed route as “... facilities which few other roads and few other Cities enjoy.”9 The station was to take up the entire block between Cherry St. (later Wooster St.) and Chapel St. The depot’s main entrance faced Union St., but access was from all four sides, the rear through a hotel on State St. The station property had previously been the old city market and canal boat landing. The parcel came per the 99-year lease of February 1, 1848 from the city to the Canal road for a nominal 25-cent annual rental on condition that it serve as a public railway station.10 Henry Austin, a popular though not formally trained local architect, had been engaged to plan three depots for the new Canal road at its intended terminal points of New Haven, Plainville, and Collinsville. The NY&NH also retained him. Whereas Austin's other stations were diminutive depots for small towns, the Elm City structure was a colossus. A 300-ft long, architecturally eclectic edifice, it mounted a short pagoda-style dome in the center and asymmetrical towers at each end. The taller one on Chapel St. was a 140-ft Italian-style campanile, a bell tower, the first in the country as part of a rail depot. Also seen as a civic structure, the station rang its bell to sound fire alarms as well as announce trains. While it was suggested that another level be added to the building to house city hall,11 Austin designed that as a separate project completed in 1862 on Church St. Below the depot bell, a four-sided, gas-lit clock, donated by James Brewster, local carriage maker and first president of the H&NH, shone to announce the time in all directions and perhaps to foreshadow the coming of more railroads to this facility. The NY&NH acknowledged the station’s $40,000 cost as its sole extravagance, a deferential gesture to the people of the Elm City. Inside were opulent parlors, “obliging servants,” and later a restaurant.12 Bold exterior form and elegant appointments notwithstanding, function was unfortunately overlooked in the platform area. The subterranean darkness, choked with locomotive heat, fire, and smoke, evoked images and memorable references to the infernal regions from travelers who descended into the canal bed covered by the rear of the station. Steps down on the Union St. side led to the NY&NH track and on the State St. side to the track for the Canal road. The finishing touches on the structure, which was in use by October 28, 1848, came early the next year but did not address the problems that would lead to two remodels in as many years and ever continuing complaints.13

[6.2.2] Thus, by the beginning of 1849, New Haven had three railroads that were functioning more or less as two. Almost immediately the two principal roads found reason for cooperation, albeit guarded. The NY&NH, not interested in freight revenue, was looking to capture as much as it could of the Hartford road’s 300,000 annual passengers to and from New York, the connection with the Western RR in Springfield creating an all-rail route from Boston. The Hartford road, content with the steamboat arrangements it had at Belle Dock, was not particularly interested in a connection with the NY&NH and feared reprisals from the competing Connecticut River boats. Its other concern was that Canal road would extend north and siphon off its Western RR traffic. The NY&NH assuredly had this fear in mind when it leased the Canal road. The NH&N would get as far as Granby, with branches to Tariffville and to Collinsville, all in 1850. The latter was for the coveted traffic of the Collins Mfg. Co. there and with an eye toward going on to Pittsfield, Mass. At that point, however, the NY&NH quietly began to help stall the NH&N. In return, the Hartford road consented to share the NY&NH’s rental payment on the Canal line, to run H&NH passenger trains into the new Austin depot instead of Belle Dock, and, by April, to suspend its own day steamer, the Commodore, to guarantee more passenger traffic on the NY&NH. This effort was supported by Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose interests in these boats were being subordinated to his investments in both the NY&NH and H&NH. By January 27, 1849, the NY&NH had extended its track from Chapel St. northward to a junction with the H&NH at the ‘tin bridge’ over the Mill River. The metal-covered, wooden deck of the bridge here gave this structure its nickname that was found elsewhere on railroad bridges outfitted similarly. On January 29, 1849, the first H&NH connection was made with a train to New York.14 The fact that the several contracts between the NY&NH and the H&NH all expired on July 1, 1869, the same date as the NY&NH lease of the NH&N was up, seems to show that the principal parties were intent as much on keeping each other in check as simultaneously reining in the Canal road.

Track 6.3: The Second Railroad Trio, 1852-1871

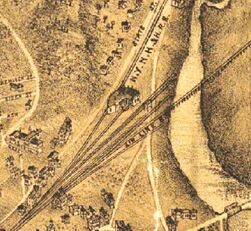

[6.3.1] New Haven’s fourth line, the New Haven and New London RR, aimed for the east in 1852. Planned largely as a link in a shoreline route to Boston, it absorbed the New London and Stonington in 1857 in order to connect with the New York, Providence and Boston RR. Similar to the NY&NH’s earlier challenges, its coastal route came with even larger obstacles. The Connecticut and Thames Rivers, initially too formidable to be bridged, had to be crossed by ferry and this gave inland routes the advantage for the next forty years. The NH&NL came into New Haven via what was then the westerly part of East Haven before this section was annexed by the Elm City in 1881. The NH&NL ran up along the east side of the Quinnipiac River and crossed it on a wooden span just above Grand St. Angling northwest through Fair Haven at grade, it continued toward the point known officially as Shore Line Jct., but also as Mill River Jct. or Tin Bridge. From here it built its own track southward to Grand St. The use of the Austin depot and this right of way were covered in a lease by the NY&NH from December 30, 1851 to the already familiar date of July 1, 1869. The New York road initially refused to sell through tickets to Boston via New London, in deference to its allied Hartford road, until the state legislature passed a bill compelling it do so. Even then it took the U.S. Supreme Court to enforce the law. The NH&NL set up an engine house, turntable, and freight facilities at the foot of Myrtle St. just below the junction on what would soon be known as Railroad Ave., rather than River St. This was on the west bank of the Mill River to which the railroad also had freight access by water, as seen on the Bailey map. Early financial difficulties would see this road reorganized as the Shore Line Railway in 1864. By 1870, with the completion of the bridge over the Connecticut River, this property would be of enough interest to be leased to the NY&NH and brought into that road's subsequent merger with the H&HN. The 'Consolidated' road, already having a monopoly on traffic to New York and not in favor with the public, was to be run by a board consisting of members of all three companies. On September 7, 1870, stockholders of the three entities gathered at separate meetings and approved the combined operation.15

[6.3.2] In 1852, the New Haven and New London RR built to Mill River Jct. From here they leased a right of way from the NY&NH, which had built up to this point to connect with the H&NH. The NH&NL laid track to Grand St. and used the NY&NH to get to the Austin depot just below. The arched bridge was called the Neck or Tin Bridge, the latter apparently for the metal-covered deck below the track for protection against fire.

[6.3.2] An 1868 view of Mill River Jct, soon to be rechristened Shore Line Jct. with the reorganization of what had become the NHNL&S by 1864 after absorbing the New London and Stonington RR. Notice the complete facilities, including the turntable which is not on the 1879 map above. Given the accuracy otherwise, it is hard to believe that the bird's-eye artist missed this. The NY&NH leased the Shore Line Rwy in 1870 and perhaps had better use for the turntable elsewhere in its growing system.

[6.3.4] New Haven’s railroads would prosper in the period from 1840 to 1870 and contribute to the city’s growth, as reflected in a near quadrupling of its population. While it had always been the state’s largest city, a position it would retain until 1930, it now had 50,840 residents to Bridgeport’s 18,969 and Hartford’s 37,180. The population grew in tandem with the proliferation of manufacturing establishments, boosted by the U.S. Civil War, providing work for citizens and attracting people from the hinterlands. The New York road double-tracked its line by 1853 and it leased the Shore Line in 1870.16 On July 1, 1869 the NH&N became a free agent agent and quickly began to rebuild and expand after years of management, some said neglectful, by the New York road. The Collinsville branch was extended to New Hartford in 1870 and over the Farmington River there in 1876 to reach the Greenwoods Co. While the Canal road still looked northwest toward Pittsfield, it had also pushed further due north. The wily Joseph Sheffield had found various ways to circumvent the enemies, allowing the Canal road to reach Northampton in 1855 and Williamsburg in 1867.17 At its southern terminus the resurgent NH&N filled in the remainder of the canal basin and erected its own facilities east of the ones it formerly shared with the NY&NH. It constructed a freight office on East Water St., a freight house, a half roundhouse and shops below, and built a dock out into the harbor beyond the original south boundary of the canal basin, which shows on maps by this time as an extension of Brewery St. This Canal dock appears on some maps as Sheffield Wharf, named for the man who was still president of the road. Built on pilings, it was 80-ft. wide and 1500-ft long and later it would be extended almost as far into the harbor as Long Wharf itself. The Canal road would spend over $300,000 on the work here from 1869 to 1871 and begin connecting with steamers New Haven and Northampton.18

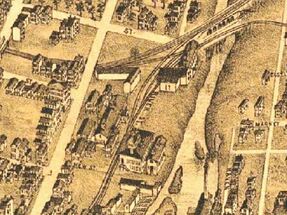

[6.3.5] The Elm City saw its fifth steam road open in 1870. The New Haven, Middletown and Willimantic RR ran its first train to Middletown on August 2. It built to Shore Line Jct. and used the NY&NH track from there, first into the Chapel St. depot and then down to the Meadow St. station in 1875. The road opened to Willimantic on April 26, 1873, having finally bridged the Connecticut River over the objections of the still-powerful boat companies.19 That opposition had arisen as early as when this road was first conceived of in the 1840s. While not unprecedented - New Haven had aided the Northampton Canal - the city assisted this project to the tune of $500,000 in bonds it guaranteed and on which $15,000 semi-annual interest was being paid by the city.20 In 1875 the road was reorganized as the Boston and New York Air Line. Linking the two named cities via a direct inland route had always been part of the vision for this road, which was referred to as the ‘Air Line’ even before its opening as the NHM&W in 1870. The new management sought to put the road into better physical and financial condition. Initially the road had made do in New Haven by farming out the work it needed to the other railroads. To lower costs, it sought to acquire its own facilities and the rumor was that it would take over the Shore Line shops that had been idled after that road was absorbed by the NY&NH in 1870.21 Instead, however, the B&NYAL soon commenced work on its own engine house and machine shop at Cedar Hill, wedged in between its line and that of the NYNH&H. While tracks here also led down to the river for some freight access by water, its main freight outlets were at Long Wharf and Belle Dock, all of which came with heavy rentals to the Consolidated. Its passenger service, of course, had to compete against the already established routes to Boston via Springfield and New London. Off to the shaky financial start for all these reasons, the B&NYAL nevertheless gradually built up a clientele and a reputation for good, fast service. In 1877, the Journal-Courier was touting the fact that its cars, locomotive power, roadbed, and courteous staff were the equal of the competition and that travelers saved some 24 miles and a half hour to an hour over the other routes. By this time it had also leased and was operating the Colchester Railway for more freight business and was seeking its own independent tidewater outlets at New Haven. By February of the next year, the Consolidated would enter into a pooling arrangement with the B&NYAL to keep it out of the hands of the NY&NE, which by now controlled the rest of the shortest route to Boston.22

[6.3.5] The Elm City saw its fifth steam road open in 1870. The New Haven, Middletown and Willimantic RR ran its first train to Middletown on August 2. It built to Shore Line Jct. and used the NY&NH track from there, first into the Chapel St. depot and then down to the Meadow St. station in 1875. The road opened to Willimantic on April 26, 1873, having finally bridged the Connecticut River over the objections of the still-powerful boat companies.19 That opposition had arisen as early as when this road was first conceived of in the 1840s. While not unprecedented - New Haven had aided the Northampton Canal - the city assisted this project to the tune of $500,000 in bonds it guaranteed and on which $15,000 semi-annual interest was being paid by the city.20 In 1875 the road was reorganized as the Boston and New York Air Line. Linking the two named cities via a direct inland route had always been part of the vision for this road, which was referred to as the ‘Air Line’ even before its opening as the NHM&W in 1870. The new management sought to put the road into better physical and financial condition. Initially the road had made do in New Haven by farming out the work it needed to the other railroads. To lower costs, it sought to acquire its own facilities and the rumor was that it would take over the Shore Line shops that had been idled after that road was absorbed by the NY&NH in 1870.21 Instead, however, the B&NYAL soon commenced work on its own engine house and machine shop at Cedar Hill, wedged in between its line and that of the NYNH&H. While tracks here also led down to the river for some freight access by water, its main freight outlets were at Long Wharf and Belle Dock, all of which came with heavy rentals to the Consolidated. Its passenger service, of course, had to compete against the already established routes to Boston via Springfield and New London. Off to the shaky financial start for all these reasons, the B&NYAL nevertheless gradually built up a clientele and a reputation for good, fast service. In 1877, the Journal-Courier was touting the fact that its cars, locomotive power, roadbed, and courteous staff were the equal of the competition and that travelers saved some 24 miles and a half hour to an hour over the other routes. By this time it had also leased and was operating the Colchester Railway for more freight business and was seeking its own independent tidewater outlets at New Haven. By February of the next year, the Consolidated would enter into a pooling arrangement with the B&NYAL to keep it out of the hands of the NY&NE, which by now controlled the rest of the shortest route to Boston.22

[6.3.6] This is the site of the New Haven, Middletown and Willimantic's original 1870 facilities at Cedar Hill. East Rock is beyond the hollow on the left, west of State St. This was the starting point for the NYNH&H's massive Cedar Hill yard. One of the streets nearby on the east side of State St. today is Lyman St., probably in honor of NHM&W founder David Lyman, after whom the Lyman Viaduct in Colchester was also named [click here and here].

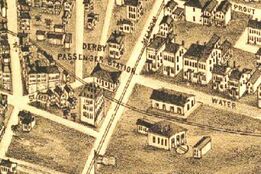

[6.3.7] New Haven’s sixth and final steam road was the New Haven and Derby RR, which opened on August 9, 1871. It had received permission in 1870 to go beyond its intended terminus on the NRR, known later as Derby Jct., and end instead in Ansonia, Derby’s northernmost borough. This was touted in the NHD&A lettering on its engines. While necessitating extra bridgework to cross and re-cross the Naugatuck River, this wise move brought it to the front door of factories like the Birmingham Iron Foundry and the Farrel Foundry and Machine Co. The Derby road was unique from the start, being born out of New Haven’s regret over the Valley traffic lost when the city spurned the Naugatuck RR’s request for a stock subscription in 1845. The NRR then headed south from Derby instead, and, lured by the offer of a free track from Naugatuck Jct. (Devon), ended in Bridgeport, the offer coming from the ever-astute NY&NH looking to get more traffic to the Empire State.23 The afterthought NH&D was expensive to build, often controversial, and required city financial assistance for which the mayor and one alderman were given seats on the board of directors. In New Haven, the NH&D built under and at grade from the West River through Custom House Square at State and Water Sts. to meet the track of the Canal road at Fair St. and thence reach the Austin depot just above and the NH&N freight facilities it initially used at the Canal dock below. The NH&D put in its own turntable below West Water St. between Meadow and State Sts. in 1871. By 1874, it filled in enough of the flats here to build its own engine house, freight depot, and a small freight yard, as well as leasing a small wharf adjoining the Canal dock and building an access track down from Fair St. to reach the waterfront.

[6.3.7] New Haven’s sixth and final steam road was the New Haven and Derby RR, which opened on August 9, 1871. It had received permission in 1870 to go beyond its intended terminus on the NRR, known later as Derby Jct., and end instead in Ansonia, Derby’s northernmost borough. This was touted in the NHD&A lettering on its engines. While necessitating extra bridgework to cross and re-cross the Naugatuck River, this wise move brought it to the front door of factories like the Birmingham Iron Foundry and the Farrel Foundry and Machine Co. The Derby road was unique from the start, being born out of New Haven’s regret over the Valley traffic lost when the city spurned the Naugatuck RR’s request for a stock subscription in 1845. The NRR then headed south from Derby instead, and, lured by the offer of a free track from Naugatuck Jct. (Devon), ended in Bridgeport, the offer coming from the ever-astute NY&NH looking to get more traffic to the Empire State.23 The afterthought NH&D was expensive to build, often controversial, and required city financial assistance for which the mayor and one alderman were given seats on the board of directors. In New Haven, the NH&D built under and at grade from the West River through Custom House Square at State and Water Sts. to meet the track of the Canal road at Fair St. and thence reach the Austin depot just above and the NH&N freight facilities it initially used at the Canal dock below. The NH&D put in its own turntable below West Water St. between Meadow and State Sts. in 1871. By 1874, it filled in enough of the flats here to build its own engine house, freight depot, and a small freight yard, as well as leasing a small wharf adjoining the Canal dock and building an access track down from Fair St. to reach the waterfront.

[6.3.8] These are the New Haven & Derby facilities as of 1879. The turntable was installed in 1871, the freight house in 1873, the engine house in 1874, and the passenger station in 1878. Truly accurate for the most part, our birds-eye artist here has erred with the Derby passenger station. It had a Mansard roof with steeply pitched sides, as shown in later photos. Compare with the roof on the Consolidated depot below.

Track 6.4: The NYNH&HRR and the 1875 Union Avenue Station

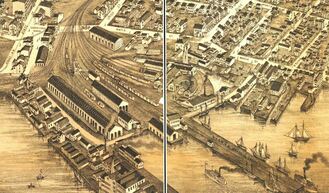

[6.4.1] The event that was to forever change New Haven and its railroads took place on August 6, 1872. This was the debut of the New York, New Haven and Hartford RR, the official merger of the NY&NH and H&NH, which had been jointly operated since August 3, 1870. The lesser-partner H&NH cooperated out of its renewed fear of competition from the recently unshackled Canal road.24 A new depot, already spoken of for years, was immediately in the offing to replace the Austin structure, still much-maligned and now greatly over capacity as well. The bustling NH&D alone was carrying as many as a thousand passengers a day into New Haven.25 The old depot was being called a ‘black hole’ by the Register as late as May 17, 1865 and in 1866 the state ordered the NY&NH to improve conditions to the satisfaction of the city and the legislature.26 These factors, plus the undoubted wish of the ‘Consolidated’ road to herald its birth, all argued for a new structure. Ground was quickly broken in an entirely new area reclaimed from the harbor just southwest of downtown New Haven. Pouring fill around the original NY&NH trestle out in the flats appears to have facilitated the process. By 1859, maps show the line sitting on a spit of land extending northeast from Spring St. and almost reaching Long Wharf. The deliberate filling of the flats and the natural harbor silting gradually diminished this inlet where the old West Creek once emptied. The Consolidated reportedly considered building south of the Austin depot, a proposition that many preferred, but decided that the parcel here was the only one large enough for its needs, according to the newspaper “for all time to come.”27 This was a wise choice for the railroad because further filling of the harbor would enable the company to expand freely and this ‘made land’ was also blessed with no buildings to dodge or streets to cross. The NY&NH purchased real estate and water lots here, the largest parcel by far coming from the Derby road, to complete its ownership of the entire waterfront from Long Wharf west to Oyster Point in 1873.28 The far-sighted New York road had begun to acquire land on the southwestern edge of the harbor as early as 1866 when it bought the Gerard Hallock estate.29 The railroad leveled the bluffs there by moving 125,000 sq. yards of material on construction trains to stabilize the marshy depot site at the foot of Meadow St. Long trains of empties used the New York 'down' track to access a temporary spur to the mud flats. As the excavation work threatened to destabilize the mansion, it was purchased by NYNH&H Master Mechanic Henry J. Kettendorf and moved across Howard Ave. to a lot he purchased.30 Using stones from Hallock’s sea wall to buttress the rail yard, a full roundhouse, turntable, and other structures would be built here by 1870 to take the place of those on Long Wharf. All the Consolidated would leave there was the car shop building, lengthened and converted for use as a freight house with additional tracks surrounding it.

Track 6.4: The NYNH&HRR and the 1875 Union Avenue Station

[6.4.1] The event that was to forever change New Haven and its railroads took place on August 6, 1872. This was the debut of the New York, New Haven and Hartford RR, the official merger of the NY&NH and H&NH, which had been jointly operated since August 3, 1870. The lesser-partner H&NH cooperated out of its renewed fear of competition from the recently unshackled Canal road.24 A new depot, already spoken of for years, was immediately in the offing to replace the Austin structure, still much-maligned and now greatly over capacity as well. The bustling NH&D alone was carrying as many as a thousand passengers a day into New Haven.25 The old depot was being called a ‘black hole’ by the Register as late as May 17, 1865 and in 1866 the state ordered the NY&NH to improve conditions to the satisfaction of the city and the legislature.26 These factors, plus the undoubted wish of the ‘Consolidated’ road to herald its birth, all argued for a new structure. Ground was quickly broken in an entirely new area reclaimed from the harbor just southwest of downtown New Haven. Pouring fill around the original NY&NH trestle out in the flats appears to have facilitated the process. By 1859, maps show the line sitting on a spit of land extending northeast from Spring St. and almost reaching Long Wharf. The deliberate filling of the flats and the natural harbor silting gradually diminished this inlet where the old West Creek once emptied. The Consolidated reportedly considered building south of the Austin depot, a proposition that many preferred, but decided that the parcel here was the only one large enough for its needs, according to the newspaper “for all time to come.”27 This was a wise choice for the railroad because further filling of the harbor would enable the company to expand freely and this ‘made land’ was also blessed with no buildings to dodge or streets to cross. The NY&NH purchased real estate and water lots here, the largest parcel by far coming from the Derby road, to complete its ownership of the entire waterfront from Long Wharf west to Oyster Point in 1873.28 The far-sighted New York road had begun to acquire land on the southwestern edge of the harbor as early as 1866 when it bought the Gerard Hallock estate.29 The railroad leveled the bluffs there by moving 125,000 sq. yards of material on construction trains to stabilize the marshy depot site at the foot of Meadow St. Long trains of empties used the New York 'down' track to access a temporary spur to the mud flats. As the excavation work threatened to destabilize the mansion, it was purchased by NYNH&H Master Mechanic Henry J. Kettendorf and moved across Howard Ave. to a lot he purchased.30 Using stones from Hallock’s sea wall to buttress the rail yard, a full roundhouse, turntable, and other structures would be built here by 1870 to take the place of those on Long Wharf. All the Consolidated would leave there was the car shop building, lengthened and converted for use as a freight house with additional tracks surrounding it.

[6.4.2] This is the NYNH&H's 1875 station. Note the Mansard roof, the steeply sloped second roof with gabled windows, which is accurately depicted for this building. Most of the land here was bought from the Derby road and filled in by the Consolidated to support the station and other structures.

[6.4.3] A wider shot of the entire Consolidated complex in 1879. Note the full roundhouse to replace the one that was dismantled at Long Wharf, and also the numerous other structures. Work on this complex reportedly started in 1869 and culminated with the 1875 station. The tiny Derby road facilities are right above those of the mighty Consolidated. The Derby depot location from 1875 to 1877 was in the small building, second in from the corner of State St., just above the 'St' in West Water St. From March of 1877 until June of 1878 it would move to structure built adjacent to the track at State and West Water Sts. The empty land in the eastern corner of State St. and West Water St. was cleared in 1873 to provide expansion space for the NH&D.

[6.4.4] The Consolidated's new, three-story station was designed in-house by C.J. Danforth, a draftsman in the engineering department and possession was taken on May 24, 1875. Its 255x75-ft size and its generous appointments were said to be on a par with the 1871 Grand Central Depot in New York City.31 The new Union Station had a center ticket office, a “commodious” baggage room on the east end, an express room on the west end, separate men’s and women’s waiting rooms and a restaurant in between. The cooking facilities and furnaces were in the basement and “dumb waiters” were used to connect with the dining room and “do the art culinary on an extensive scale.” By 1877, the busy restaurant would be going through 150 lbs of roast beef, 60 to 75 chickens, 100 gallons of coffee, 50 gallons of tea, 60 to 80 gallons of oysters when in season, plus sandwiches and desserts.32 Outside, a 1000-ft covered platform protected passengers boarding trains in the open air in the rear where, as a correspondent from The New York Times said, “the blue water comes up to the very track of the road.” This was literally a breath of fresh air in stark contrast “to the miserable old rookery, on Chapel St., which has excited the disgust of so many.”33 Additional stub-end tracks and covered platforms met the new depot on both ends. The exterior was faced with 750,000 pressed bricks from Hartford and North Haven, and was trimmed in Portland brownstone. A Mansard roof, in vogue at the time, adorned the top with short end towers and a taller clock tower in the center facing Union Ave., a two-block-long street created to angle southwest from the foot of State St. to the new station. The building’s two upper levels housed NYNH&H offices. While the new station was hailed as a physical improvement over the old one, there were perennial complaints that the location was less convenient for the public. Initially, no streetcar lines could even provide front-door access. While Meadow St. would be widened later and extended as an approach to the station, wooden planks were laid down in the meantime for pedestrian access. Hack carriages had to struggle in the sandy soil. To mitigate this, the railroad ran shuttle trains from Fair Haven and from the ‘old depot’ as the Austin structure, still in use, was now called. Initially, the fare on the ‘scoot,’ was five cents, both ways, but was later raised to ten cents inbound.34

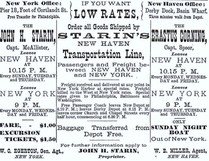

[6.4.5] So the situation was as of mid-1875 that the Consolidated, its leased Shore Line road and the still-independent Canal and Air Line roads were all using the new Union Station. Because of its solitary entrance from the west, the Derby road was the only one left out of this arrangement. Access was still possible by crossing Custom House Square and backing down but this was cumbersome and dangerous with the trains of five other lines funneling into the NYNH&H station. The NH&D, with its four or five daily trains, could also still have used the Austin depot, but this too did not happen. The Derby road chose instead to stay independent and rented office and depot space at 211 West Water St., just west of State St. and across from its track. This single diversion of passengers from the Chapel St. station was said to have caused a considerable drop in use of the street car line that served the ‘old depot.’ While most of its passenger traffic was local, Derby road customers who needed to make connections to Union Station a block south did so easily on foot. Baggage was transferred free of charge. Because passengers had to cross West Water St. to access trains from the new location, the station was moved to a building on the southwest corner of State, right on Custom House Square.35 To save the rental costs, the NH&D opened its own passenger depot in June, 1878. Tucked into the southwest corner of Meadow and West Water Sts., it was a two-story brick structure, 70x22 feet, with three rooms for offices upstairs.36 The ground level was said to be arranged similarly to Union Station. The exterior sported a Mansard roof, perhaps deliberately imitative of the mighty Consolidated’s new depot. Pursuant to the sale of the land for that depot, the Derby road got its lease of the right to cross over Consolidated tracks to reach the harbor changed from annual to one in perpetuity on October 9, 1873.37 It laid its own track from Fair St. down to Brewery St. and leased a small dock there on the westerly edge of Sheffield Wharf in 1874 and expanded it in 1877.38 It was here that the New York-based ships the John H. Starin line would begin to dock, forming a through route from the Valley to the Empire City via the NH&D.

[6.4.4] The Consolidated's new, three-story station was designed in-house by C.J. Danforth, a draftsman in the engineering department and possession was taken on May 24, 1875. Its 255x75-ft size and its generous appointments were said to be on a par with the 1871 Grand Central Depot in New York City.31 The new Union Station had a center ticket office, a “commodious” baggage room on the east end, an express room on the west end, separate men’s and women’s waiting rooms and a restaurant in between. The cooking facilities and furnaces were in the basement and “dumb waiters” were used to connect with the dining room and “do the art culinary on an extensive scale.” By 1877, the busy restaurant would be going through 150 lbs of roast beef, 60 to 75 chickens, 100 gallons of coffee, 50 gallons of tea, 60 to 80 gallons of oysters when in season, plus sandwiches and desserts.32 Outside, a 1000-ft covered platform protected passengers boarding trains in the open air in the rear where, as a correspondent from The New York Times said, “the blue water comes up to the very track of the road.” This was literally a breath of fresh air in stark contrast “to the miserable old rookery, on Chapel St., which has excited the disgust of so many.”33 Additional stub-end tracks and covered platforms met the new depot on both ends. The exterior was faced with 750,000 pressed bricks from Hartford and North Haven, and was trimmed in Portland brownstone. A Mansard roof, in vogue at the time, adorned the top with short end towers and a taller clock tower in the center facing Union Ave., a two-block-long street created to angle southwest from the foot of State St. to the new station. The building’s two upper levels housed NYNH&H offices. While the new station was hailed as a physical improvement over the old one, there were perennial complaints that the location was less convenient for the public. Initially, no streetcar lines could even provide front-door access. While Meadow St. would be widened later and extended as an approach to the station, wooden planks were laid down in the meantime for pedestrian access. Hack carriages had to struggle in the sandy soil. To mitigate this, the railroad ran shuttle trains from Fair Haven and from the ‘old depot’ as the Austin structure, still in use, was now called. Initially, the fare on the ‘scoot,’ was five cents, both ways, but was later raised to ten cents inbound.34

[6.4.5] So the situation was as of mid-1875 that the Consolidated, its leased Shore Line road and the still-independent Canal and Air Line roads were all using the new Union Station. Because of its solitary entrance from the west, the Derby road was the only one left out of this arrangement. Access was still possible by crossing Custom House Square and backing down but this was cumbersome and dangerous with the trains of five other lines funneling into the NYNH&H station. The NH&D, with its four or five daily trains, could also still have used the Austin depot, but this too did not happen. The Derby road chose instead to stay independent and rented office and depot space at 211 West Water St., just west of State St. and across from its track. This single diversion of passengers from the Chapel St. station was said to have caused a considerable drop in use of the street car line that served the ‘old depot.’ While most of its passenger traffic was local, Derby road customers who needed to make connections to Union Station a block south did so easily on foot. Baggage was transferred free of charge. Because passengers had to cross West Water St. to access trains from the new location, the station was moved to a building on the southwest corner of State, right on Custom House Square.35 To save the rental costs, the NH&D opened its own passenger depot in June, 1878. Tucked into the southwest corner of Meadow and West Water Sts., it was a two-story brick structure, 70x22 feet, with three rooms for offices upstairs.36 The ground level was said to be arranged similarly to Union Station. The exterior sported a Mansard roof, perhaps deliberately imitative of the mighty Consolidated’s new depot. Pursuant to the sale of the land for that depot, the Derby road got its lease of the right to cross over Consolidated tracks to reach the harbor changed from annual to one in perpetuity on October 9, 1873.37 It laid its own track from Fair St. down to Brewery St. and leased a small dock there on the westerly edge of Sheffield Wharf in 1874 and expanded it in 1877.38 It was here that the New York-based ships the John H. Starin line would begin to dock, forming a through route from the Valley to the Empire City via the NH&D.

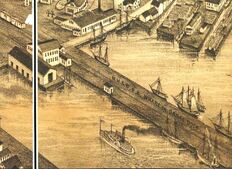

[6.4.6] This shot shows the head of Long Wharf (left) and also the Canal road facilities (right) on the east side of the basin that was filled in back in 1869-1870. Note the absence of the turntable and domed engine house that the NY&NH and the NH&N built jointly in 1848. The only NYNH&H building left is long freight house, formerly the car shop.

[6.4.7] The east side of the former canal basin is nearly all filled in and holds the extensive NH&N facilties. A Starin line steamer may be heading for the small Derby dock. A newspaper article says that, after a winter ice disruption, the Starin line was once again delivering freight "at her old dock, Derby railroad pier." The NH&D leased pier rights and land for a track to it on October 9, 1873 from the Consolidated and built the wharf early in 1874. The street running across the bottom of the old canal basin begins now to show on maps as Brewery St., continuing out from the 'mainland.' The city made this name official in 1882.39

[6.4.8] At left is an ad from the 1879 Price & Lee city directory, mentioning the free coach to take passengers from the NH&D station and the New Depot, as the 1875 Union Station was known, and to the Starin ships at the Derby dock. In 1875 and 1879, the Starin dockage and freight house capacity would be increased with the extension of the single pier and an additional pier to its right. Compare with the 1888 map in Hopkin's Atlas of the City of New Haven.40

Track 6.5: The 1880s - New Haven’s Gateway to the West

[6.5.1] The ever-expanding Consolidated would prosper in the 1880s, while warily guarding its monopoly on traffic to New York City, the subject of public complaint as early as 1866. In 1871, a general railroad law was passed allowing the formation of new railroad companies without the legislative charters that had been the custom back to the 1830s.41 This move to allow more competition in the railroad industry was intended, in part, to assuage opposition to the merger that permitted the creation of the Consolidated and expanded its power when many thought that just the opposite was needed. The idea for parallel went back by some reports to the Danbury & Norwalk's LeGrand Lockwood, on whose behalf Samuel E. Olmstead began to act in 1866, his name later becoming synonomous with the movement. Over the next three decades, at least eight companies were organized, some morphing into successors and proposing to build more or less the same northerly inland line between New Haven and New York. The conflict became complicated enough at one point that two of the contenders, the New York & Connecticut Air Line and the Hartford & Harlem, went on to battle each other until they both expired.42 To reduce the odds that existing roads might be used in the parallel scheme, the Consolidated began a policy that might be called 'defensive acquisition.' Among the railroads it took over in this decade were the Boston & New York Air Line that it leased in 1882 to forestall the intended link between its namesake cities and the Canal road, with its convenient connection to the NH&D right in New Haven, that it leased again in 1887. With five of the six New Haven railroads thus captured, the Derby road attained a pivotal importance as the only remaining independent route out of New Haven. Always touted as the ‘Gateway to the West’ by its promoters, the 'Little Derby' and the Elm City watched the completion of the New York and New England RR westward to the Hudson River in 1881 with great interest. The NY&NE, controlled by New York investors including Jay Gould, seized the opportunity it saw here, buying up the stock of the Housatonic RR and consequently having it get control of the NH&D on July 12, 1887.43 The city of New Haven, the largest stockholder, rejected higher offers in order to keep the Derby road out of the hands of the Consolidated and to secure the promised western connection. Plans were already in place to extend the NH&D up into Huntington, today the town of Shelton, to meet a branch of the HRR to be built down from Botsford into Monroe. Interestingly, this new trackage, known shortly as the 'Extension,' would have added value when the American Bell Telephone Co. began using it for new Boston-New York City long distance wires in 1888. The original NH&D had already been serving as communications route from the Elm City to Ansonia since 1877 for the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Co., and the ATT line to Ware, Mass. was begun "appropriately enough, in New Haven at the depot of the Derby Railroad" on August 11, 1886.44 Soon there would also be poles on the other side of the NH&D, these carrying the wires of the Southern New England Telephone Co., headed by Morris Franklin Tyler, an NH&D director and son of its earlier president.45

[6.5.2] The Derby road’s new westward thrust was also reflected in its property in New Haven. For public safety reasons, the city had grappled for years with ways in which the NH&D, while maintaining its independence from the NYNH&H, could move its operations base west of Commerce St. and run to the wharf only during nighttime hours. Nearby land for a new yard was acquired -- discreetly. The Consolidated was not above spoiling such plans, such as the 1899 Granby land grab to block the Central New England’s line to Springfield would show.46 Jabez Bostwick, who succeeded Charles P. Clark as president of the NY&NE in December of 1886, purchased much of the land personally and later transferred it to the NH&D.47 Permission to abandon the old depot location was given by the railroad commissioners on January 1, 1888. The new yard complex was in the area enclosed by Cedar, Silver, West Water, Minor, and Commerce Sts. On the north side Hill and Lafayette Sts. were closed at Silver, which was extended to Commerce St. to move traffic around the block. The railroad commissioners kept Liberty St. open and ordered a bridge to go over the yard here to pacify residents who complained at hearings about the street closings. In spite of what probably were sincere efforts on the Derby road's part, legal complications delayed the fulfillment of its promises to the neighborhood and caused some animosity toward the NH&D and the HRR.48 At the southwest corner of Commerce and Silver Sts. the NH&D built a three-story building for a new passenger station and offices above. It was from here that an inspection train ran up the newly completed Extension on October 14, 1888. A wonderfully detailed description of the new line and the challenges of its construction ran in the Register, and said that monumental project began on August 21 and the last rail was laid at 3:30 on October 3.49 On Wednesday, October 17, an inaugural train departed at 10:30 a.m. William H. Stevenson, the NH&D president as well as the HRR’s vice president and general manager, proved himself to be something of a P.T. Barnum as well. The Wheeler & Wilson band from the HRR’s headquarters town, Bridgeport, was on board the flag-and-bunting-decked, four-car train, as well as railroad officials, local dignitaries, and newspaper men. The entire train reportedly disembarked at Shelton, then the only stop on the new line, for music and festivities witnessed by a crowd of 500 residents. The piece de resistance was yet to come. The technical meeting point of the two railroads was about four miles above Derby Jct. but, apparently for effect, Stevenson chose a spot a mile and a half north for a spike-driving ceremony. This was overlooking the Housatonic River at a 200-ft elevation, the magnificent vista enhanced by the beautiful autumn foliage. At precisely 12:00 noon Stevenson drove two spikes, to the accompaniment of music, huzzahs, and celebratory cannon fire. One spike was of solid silver and, in a patriotic tribute, the other was a gold-plated spike of copper made from the nails of the venerable U.S. warship Colorado, which had recently burned off the coast of Port Washington, New York [click here]. The spikes were then lifted to be preserved at the Housatonic offices in Bridgeport.50 The train resumed its course, passing the point opposite Zoar Bridge where a station would soon be named ‘Stevenson’ by grateful locals, going on to Danbury for festivities, thence down to Bridgeport, and back to New Haven later in the evening.

[6.5.3] Even as the hoopla was fading, work in New Haven was proceeding. Instead of tearing down the 1878 passenger station, the NH&D earmarked it to serve as the freight office and moved to the south end of the new building. With the Extension certified as safe by the railroad commissioners, the composite structure was expected to be fully opened with regular train service commencing on November 26, 1888.51 The shed over the passenger platform behind was said to cover “several thousand” feet of track. On February 19, 1889, a 73-ft freight house was opened facing West Water St. behind the freight office. A site further along at West and Thorn Sts. was also acquired for a new four-stall engine house and turntable, which were in place by May, 1890.52 Interestingly, some of this land was owned by Morris Franklin Tyler.53 To cement their relationship further, the Housatonic leased the NH&D on July 9, 1889, effective the following day.54 NHD&A engines 1 through 5 would be renumbered into the HRR roster as 47 through 51 while newly purchased engines were numbered 30, 31, 33, 34, and 35. The new ones, and presumably the old, were now lettered simply as NH&D. Early in 1891 the #30 was delivered and the other 4 were still on order, as well as 10 new passenger cars and 100 new freight cars, all expected to be delivered by April 1 at a cost of between $175,000 and $200,000.55 Ansonia’s nominal loss of status as Derby road terminus was compensated for by its increased prosperity as a branch of the HRR system. Expansion of the freight yard by filling in the land and laying additional tracks "to take care of the large increase of business at that point" was underway in 1890 and was expected to be finished by January 1, 1891. Work here also included a new turntable and there was talk of the NH&D recrossing the Naugatuck River to extend to Seymour or even Waterbury.56 A Register article shortly after the Extension opened said that Ansonia businesses were saving $10 per carload via the new routing and that this would "plough a very big furrow in the Consolidated road's traffic" in the lower Valley.57 Merchants in New Haven were “astonished” at the benefits. Lower shipping costs, easier access to the NH&D freight house in contrast to the congestion at Long Wharf, and even more politeness from the Consolidated, which was now facing some real competition, prompted one customer to say that “now everything is as nice as pie.” This increased traffic on the NH&D, with its tidewater connection to New York via the Starin line, had become more valuable than ever, to be protected from those who wanted the removal of the tracks through Custom House Square or any other change that would make the NH&D less competitive with the Consolidated.58 There was a substantial increase in passenger traffic as well. By 1892, 50 trains per day were using the NH&D terminal, a four-fold increase from 1887.59 A 500-ft freight house had been opened on Silver St., a restaurant was operating in the passenger station, hackmen were 'red-lined' at the curb outside, and plans were being made to double-track to the West River and possibly beyond. Permission from the railroad commissioners came in May of 1892 to take more property to expand the NH&D yard.60 All of this brought it ever closer to confronting the Consolidated, which displayed a seeming indifference toward the competition prospering right across Union Ave.

Track 6.6: The Consolidated Empire Strikes Back

[6.6.1] The staid demeanor of the Consolidated would soon change. It too was looking to expand here. Whereas it had once offered the lot in front of the Meadow St. station to the city on condition it be made into a park - a proposition the city declined - by 1891 the offer was not only withdrawn, but more land was being sought.61 The Consolidated’s plan was to build a new, larger station, and to convert the old one, “crowded from basement to attic,“ into an office building.62 An addition had already been put onto the west end of the building, at the direction of Charles P. Clark, newly installed as president in March of 1887. This enabled him to move the executive offices from Grand Central Terminal to New Haven, an operation completed on November 26, 1887. The addition included a new assembly hall for the stockholders, first used on December 21, 1887 for the annual meeting.63 These changes aside, the space crunch continued, with a new station still seen as the ultimate answer. The old Chapel St. location was even rumored for the site of this new station.64 Urgency, however, was injected into all of these plans when a fire on March 19, 1892 largely destroyed the third floor of the Meadow St. station.65 To get by for the time, the Consolidated re-roofed the second story leaving only the two patched-up end towers above it, and redeployed office staff as necessary. The spatial pressures here mirrored the tension on the tracks. As of April 1, 1887, the Consolidated had put itself in direct competition with the HRR/NH&D by leasing the Naugatuck RR. Not surprisingly, the 1880 NH&D/NRR pooling agreement was discontinued as of October 1, though apparently this was mutually agreed upon.66 There was also talk of the Consolidated attempting to renege on the agreement allowing NH&D trains to cross its tracks to get to Starin's Wharf. Late in 1887, "a frog" arrived that was used to join the NRR to both tracks of the NYNH&H at Naugatuck Jct., today's Devon, thus restoring a connection to New Haven abandoned when the NH&D opened in 1871.67 And, should it become necessary to further marginalize the value of the Derby road, the old NRR plan for a line from Woodmont to Wheelers Farm was dusted off at this time.68 Land issues and interchange difficulties both in Bridgeport and Norwalk also fueled the hostility as did the 1889 legislative battle wherein the HRR lost a bid to essentially become one of the last parallels and expand its system to better compete with the Consolidated.69 Public opinion was, of course, overwhelmingly with the underdog HRR. Midway in 1892, the simmering pot of issues boiled over with a stunning series of events to deal with an HRR that then-new directors J.P. Morgan and William Rockefeller recognized as no longer a 'streak of iron rust' but rather 'a thorn of the most formidable kind.'70 On Friday, June 10, they reportedly paid a large premium to purchase majority control of HRR stock. The New York syndicate that sold out used the excuse of uncovering some HRR financial irregularities to explain its hasty exit.71 On the following Wednesday, Stevenson and the rest of the HRR officers and managers resigned and were replaced on legal documents by Morgan, Rockefeller, and other NYNH&H officials.72 On June 18, just days later, the Courant reported that “the first complete Consolidated road train to run over the Housatonic went up the Derby branch from New Haven Saturday."73 The Consolidated lease of the HRR was effective on July 1.74 Next, New Haven’s board of aldermen received a petition with several startling proposals. These included the construction of a new Union Ave. above the old, the discontinuance of the streets below it for yard expansion, and the elimination of NH&D tracks east of Meadow St. by November 1, with access to the Derby terminal thereafter only from the west.75 And, finally, the NYNH&H petitioned the railroad commissioners for permission to construct a new connection, dubbed the West River branch, to bring Derby line passenger trains into Union Station. The customary maps, undoubtedly drawn up earlier, were submitted to the commissioners with the application on July 16 and approval was given on August 1 after a hearing in New Haven on July 22.76 While the Consolidated had every right to move quickly, the breakneck speed, from costly purchase, to new Union Ave., to hasty lease, to action on the West River branch, all within six weeks, not to mention the personal involvement of Morgan and Rockefeller, seems to indicate premeditated planning and a real urgency to get rid of the HRR and its leased NH&D.

[6.6.2] The Consolidated also lost no time in assimilating the Derby road facilities. The aforementioned West River branch was in place by October 27, 1892, running from a switch just past Lamberton St. up along the Boulevard to a west-facing connection with the NH&D.77 Due to sinking in the West River meadow, this link was not certified as safe by the railroad commissioners until November and not used for passenger service until December 11, 1892.78 On that day trains ceased running to the Derby depot and began to come instead to two pocket tracks on the west side of Union Station. On December 13, 1892 the HRR and NH&D lines officially debuted as the NYNH&H’s Berkshire Division. The two daily trains each way for Pittsfield would now use the NH&D route from New Haven instead of the HRR line from Bridgeport as they had since 1850. This, of course, would result in crowing on the part of the Elm City about their new status and some complaint from the Park City as this being a violation of the HRR charter, in spite of connecting service still being maintained at Botsford.79 With the east leg of the wye at the West River installed shortly thereafter, later timetables show some trains backing into or out of the Meadow St. station to reverse direction as needed from here.80 The river connector had been suggested by the city several years earlier to eliminate the NH&D track through Custom House Square. The Consolidated had been amenable to these changes, and even to allowing wharf access through its yards, but the NH&D, fearing it would be “swallowed up,” had declined. Now its track to Fair St. was removed, as promised, and the line was stub-ended on the west side of Meadow St.81 The Consolidated also enlarged the Silver St. freight house with a 500-ft addition, and began utilizing it for outbound freight and, in turn, using the Long Wharf freight house only for inbound shipments.82 A new interlocking tower to control the tracks and the yards west of Union Station went into service on June 19, 1893.83 The Liberty St. bridge, in a limbo of legalities since 1888, was also finally completed by the Consolidated late in 1892.84 The last dangerous grade crossing, at East Water St. between State and Union Sts., was addressed shortly as well. With the Derby track underneath gone and an easier grade for an overhead bridge now possible, the span over the Consolidated’s tracks would open on September 24, 1894.85

[6.6.3] As if timed to crown its conquests, the Consolidated now unveiled a new general office building. It had been decided, especially after the 1892 fire, that a new office facility was a higher priority than a new station. At first it was going to be built in the block bounded by Meadow, Portsea, Lafayette Sts. and Columbus Ave. but the new Union Ave. cut through here.86 The block on the other side of Meadow St. now best fit the bill. It was mostly owned by the Consolidated except for the northerly NH&D parcel with repair shops and storage tracks. The pressing need for this final piece of the only property available for the new GOB may also have played a role in the Morgan/Rockefeller blitz in June of 1892. Ground was broken almost immediately in August, with the NH&D parcel not quit-claimed by them to the Consolidated until October 1.87 By that time, a 4,000-lb steam hammer was already driving piles 40 feet down into the ‘made land' and advancing toward the Derby facilities that had to come down immediately.88 When it opened on January 1, 1894, the four-story, L-shaped, GOB structure stretched 200 feet long on the east side of Meadow St. and 230 feet on the south side of West Water St. At a rough cost of $400,000, the fireproof building contained 125 rooms, sufficient to relocate the rest of the general offices from New York at this time. The first floor went to the operating department; the second to the traffic department and executive offices; the third to engineering and purchasing; and the fourth to the “several hundred clerks” of the accounting department. Described as the “handsomest railroad office in New England,” the exterior facade was of New Jersey buff brick and trimmed with East Haven brownstone. The southern tip of the ‘Yellow Building’ looked conveniently over toward Union Station. On the northern apex facing the NH&D station, the 0.00 marked the base mileage point of the NYNH&H’s newly christened Berkshire Division.89

[6.6.4] The Derby depot, though used to receive passengers at least once when a washout at the West River wye disrupted service to Union Station, was occupied by the freight auditing department until the GOB opened.90 The station was then refitted to debut on December 28, 1896 as the first railroad YMCA in New Haven.91 The YMCA started ministering to railroad workers and their families as early as 1868 and the first railroad branch opened in Cleveland in 1872. In New Haven, notices of 'religious meetings' involving the YMCA are found as early as 1878.92 The movement combined respect for the railroad worker and provided him with a ‘home away from home’ while caring for his educational, spiritual, and recreational needs. It also promoted sobriety in an era when alcohol-related safety problems were a serious concern. The Vanderbilt family led the way with funding for the national effort and with a branch for New York Central RR workers. NYNH&H employees had met informally for several years and, after the Consolidated absorbed the Canal road in 1887, they had asked for the use of its old freight office on East Water St.93 The matter languished until Pres. Clark got involved. The Derby depot was spacious and perfectly located. A large reception room, smoking and reading rooms, bathrooms, and a bowling alley were created on the first floor. The second floor held an assembly room and offices, while the third floor had 20 small bedrooms for railroad employees whose runs ended at Union Station. At the opening, Clark spoke of the “comfort, rest, amusement, and instruction” the facility would provide and Vice Pres. Hall said that a new era of corporate concern was bringing “intelligent capital and intelligent labor” together here. They both stressed that discrimination by race or religion would not be tolerated. The pool table, notorious for its unsavory association with drinking and gambling, came later when it became more socially acceptable. In September of 1929, a Cedar Hill RR YMCA would open in rented space at 1386 State St. in New Haven at the corner of Rock St. It had two floors of bedrooms upstairs and a lounge with reading, writing and recreational facilities on the main floor. The railroad later put up its own building, which is still standing in 2018 at 1435 State St. It was dedicated on June 30, 1945 and opened on July 2.94

Track 6.7. The Austin Depot Fire and Aftermath